A Short History Lesson That Won't Be Found in Florida's Social Studies Textbooks

A walk through a sugar plantation and its legacy of slavery

[The following story about the 19th-century Bulow Sugar Plantation originally appeared last May. With some new edits it bears repeating now to underscore what Florida is trying to erase from grade school-level social studies teaching. Specifically, the state, under directions from Governor Ron DeSantis, increasingly seeks to remove any mention of subjects that have been decided would cause distress in students and indoctrinating to beliefs that could be explained in less dira and radical terms. In the context of teaching the history of the Bulow sugar plantation that would be the horrifying subject of Florida’s history of slavery. The signs along the plantation’s trail, written by the Florida State Parks Department, give an example of how the land, its owner, and the people who worked there would be portrayed under these orders.]

Bulow Plantation is one of Florida’s better-known authentic landmarks that my GPS assures me is right off the Old Kings Road. If it is, I keep missing it. The third time down the road I turn into the Bulow RV Resort, thinking it has to be nearby. Except it’s not but the nice woman in the resort’s office next to the tiny swimming pool packed with happy-looking retirees, gives more precise directions to a nearby dirt lane that looks more like a cow path than the entrance to a major historical site. At least seven minutes of slowly rumbling over potholes open into a clearing and the remains of the Bulow Plantation one of the 19th century biggest sugar plantations Bulow Plantation.

A short history of the plantation: In 1821, Charles Bulow brought 300 of his slaves down from his family’s plantation in Charleston, South Carolina, to this wild part of the country with the purpose of establishing a profitable sugarcane business. Sugar was in huge demand around the world, and the French, Spanish, and English colonists in the Caribbean were making a fortune. The American South held all the ingredients to match the islands—fertile soil, an agreeable climate, and an abundant supply of slaves.

Bulow bought 4,675 acres along a tidal basin that gave a direct route to coastal ports. His slaves hacked out 2,150 acres. The majority of the plots would be for cane and the rest for insurance crops—rice, indigo, and cotton. The slaves also built a home for Charles, cabins for themselves, and several outer structures for horses and farm animals, grain, and equipment storage. A large sugar mill constructed from stone cut in the nearby coquina quarry was situated a mile or two away from the main house. The plantation had yet to be completed when Charles died two years later, some records attributing it to yellow fever, given the surrounding mosquito-infested marshlands.

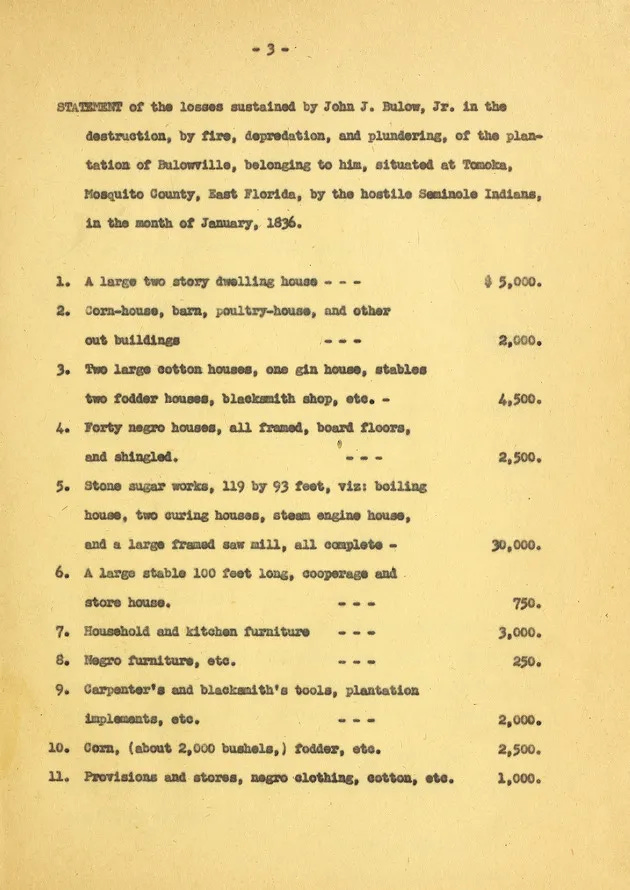

His teenage son, John, was summoned from his Paris school. Smart and ambitious, and with the help of an experienced foreman, he further expanded the plantation, buying another hundred or so slaves to help increase sugar production. All went well until the Second Seminole War. On January 11, 1836, the Seminoles burnt the entire plantation and its crops to the ground. John retreated to the family’s St. Augustine townhouse. His slaves were housed in a squalor camp on a nearby island where other plantation owners had sequestered their slaves during the crisis. John petitioned the government to provide restitution, but he died months later at the age of 26. There is no record about what caused his death (a broken heart was one speculation). Nothing is known about what happened to the Bulows’ slaves.

The ruins of the Bulow Plantation are maintained by the Florida State Parks Department. They cleared a path through the forest that swallowed the plantation after it was abandoned. The path winds from one ruin to the next:, past the traces of the mansion, to the vast scorched sugar mill complex, and over to the Bulows’ spring house.

Along the way are illustrated signs, written from John Bulow’s point of view. The text gives precise information about processing the cane. Bulow’s slaves tended to about 1,000 acres of cane and produced 2,000 barrels of sugar each year.

John also gives some hints about his life as a very social young man in his early twenties, possessed of enormous wealth, a fine Paris education, a commodious house stocked with the best wine, and a library full of novels. He fished and hunted and, according to accounts from his contemporaries, became quite famous for lavish parties and hosting famous guests.

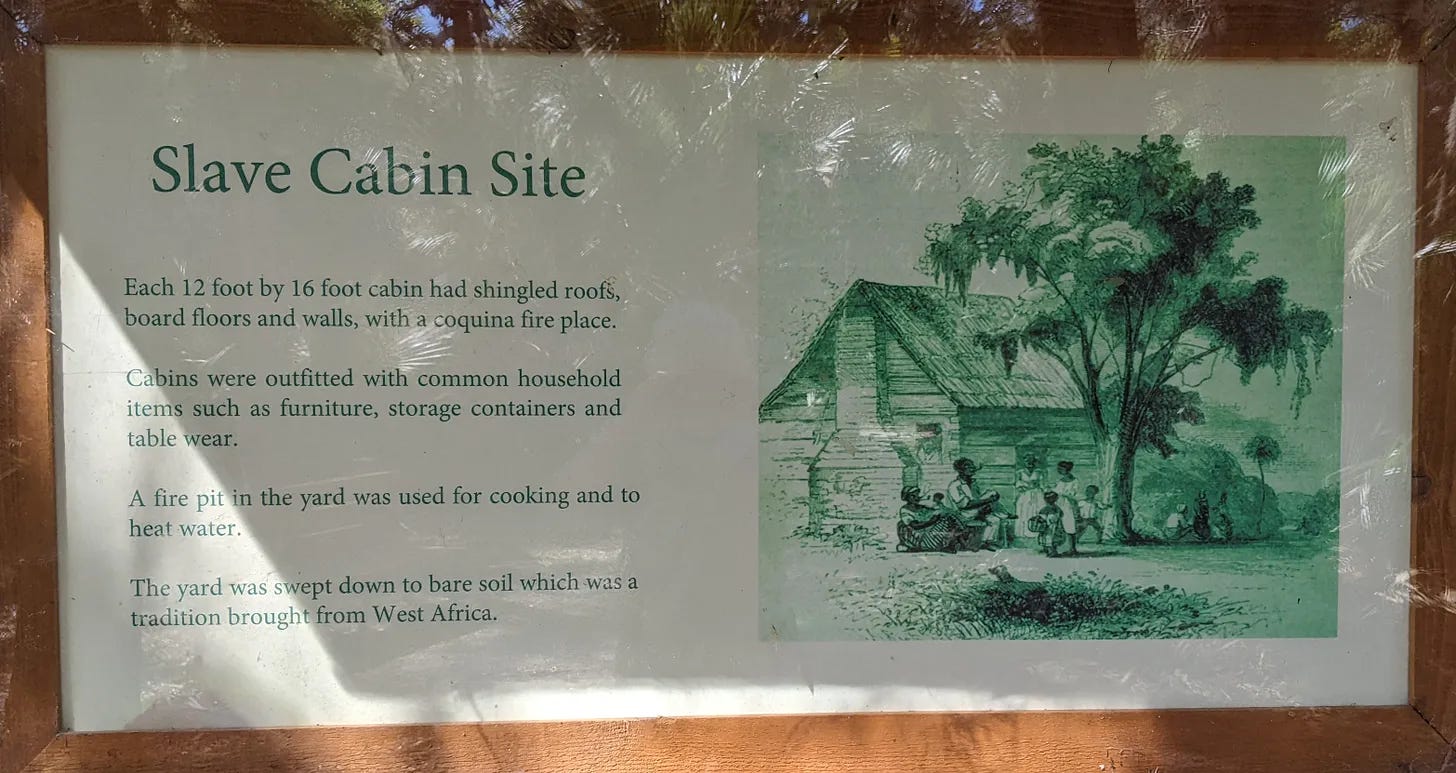

Every now and then there are hints of how his slaves lived and were treated.

Finally, the path leads around the area where the slave cabins once stood. They are all gone, but the footprint of one is marked by four wooden posts measures 12’ x 16,’ about the size of a modern tiny house.

The path ends back in the parking lot, where I find a picnic table to sit for a spell. The profound quiet is unnerving, how lacking in the thwacking sound of the harvest, the mill’s machinery rhythmic smashing of the stalks and its chimneys spewing thick, sugary, acidic smoke. Above all, what’s missing is the din of thousands of human voices that these acres once contained and the reality of how deadly the sugar industry was for slaves. It is not conceivable that a burial ground wouldn’t be somewhere under the well-maintained path.

The lack of nutrition, hard working conditions, and regular beatings and whippings meant that the life expectancy of slaves was very low, and the annual mortality rate on plantations was at least 5%.—Life on a Colonia Sugar Plantation

The silence is only broken when a gaggle of young children burst off the path. Their parents lag behind and let them run off the last of their energy. They gather in the clearing where John Bulow’s mansion stood until the Seminole Indians burnt it down during the Second Seminole War of 1836.

One of the women offers her take on what she learned at the Bulow Plantation.

“It’s such a romantic place, isn’t it?”

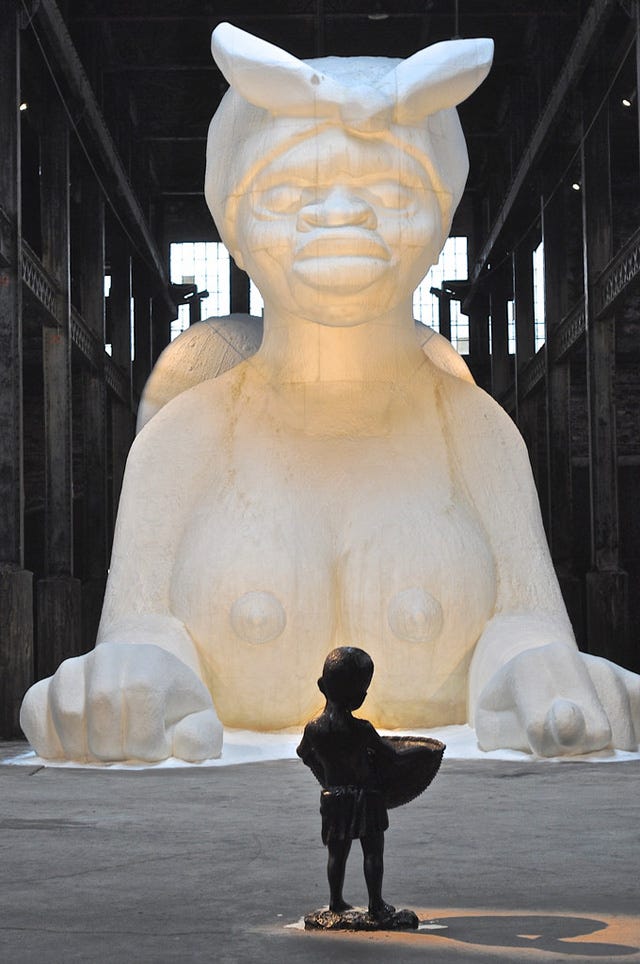

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the centerpieces of many tables at royal and wealthy people dinners was something called a subtlety, a sculpture made of sugar. The amount of sugar used in these fabled decorations was only made possible through the proliferation of large sugar cane plantations and the slave trade to the Americas. It remained an expensive ingredient and the lavish decorations were a sign of the host’s fortunes and social standing.

In 2014, artist Kari Walker created her own sugar subtlety in the ruins of the Domino Sugar Factory on the Brooklyn waterfront. It is a tribute to the human cost of producing sugar.

Thank you for sharing this. It's so easy to "forget" the horrifying history of a beloved part of our day-sugar in our coffee or tea. Thank you for this reminder and encouragement to seek out the truth behind the historical monuments and places in our communities and whether or not they are telling the whole story.

Thank you for your brave foray, literally and figuratively, into the little known woods and sad, often whitewashed history of this sugar plantation. Keep writing and shedding light on these subjects. I appreciate you and always learn something new at your “table”.