One of the books I pulled out to organize my rambling thoughts for last Tuesday’s post was Cleora Butler’s cookbook, Cleora’s Kitchens: The Memoir of a Cook & Eight Decades of Great American Food. Published in 1985, the book has been singled out since then for how it illustrates the continuing influence of African American cooking beyond its Southern roots. Butler’s recipes span 70 years, flowing from a plantation where her great-grandparents were enslaved through to the oil-rich high society of Tulsa, Oklahoma.

My copy of Cleora’s Kitchens has a broken spine, many stained pages, and an abundance of scrap paper marking where to find dishes I have repeatedly returned to for family meals and parties. This time around, I pondered Butler’s opening memoir where, after several careful reads and attempts to diagram her family history, I began to truly appreciate its subtle revelations of how growing up Black in America affected the arc of her professional history.

It would be more effective if I visualize it for you. Take a look.

Buck Manning, Butler’s great-grandfather, was the son of his owner. Her great-grandmother Lucy Ann was the plantation’s cook. They were taken by their owner from Mississippi to a new plantation in Waco, Texas, where cotton was beginning to flourish.

Their first born, Allen, Butler’s grandfather, “grew up in the plantation’s ‘big house’ amid the pots, pans and soup ladles where his mother worked.” The family was freed in 1865 (probably on Juneteenth) and Buck’s father presented him with 350 acres of the plantation, of which 50 went to Allen when he married Bettie Sadler. Allen and Bettie’s first born was Butler’s mother, Maggie. Taught by her father and grandmother Lucy, Maggie took over the kitchen chores for the growing family by the time she was 12.

At 18, Maggie married Joe Turner in 1898. They lived in a house allotted to him by the white farmer whose land he tended and who he chauffeured around Waco. Maggie became their family’s cook and seamstress. Butler was born in 1901. “….the excitement of a new century permeated the air. The [year] just passed, though turbulent, has stood the Manning and Thomas families well. The children coming into the world were the grandsons and granddaughters of former [sic] slaves.”

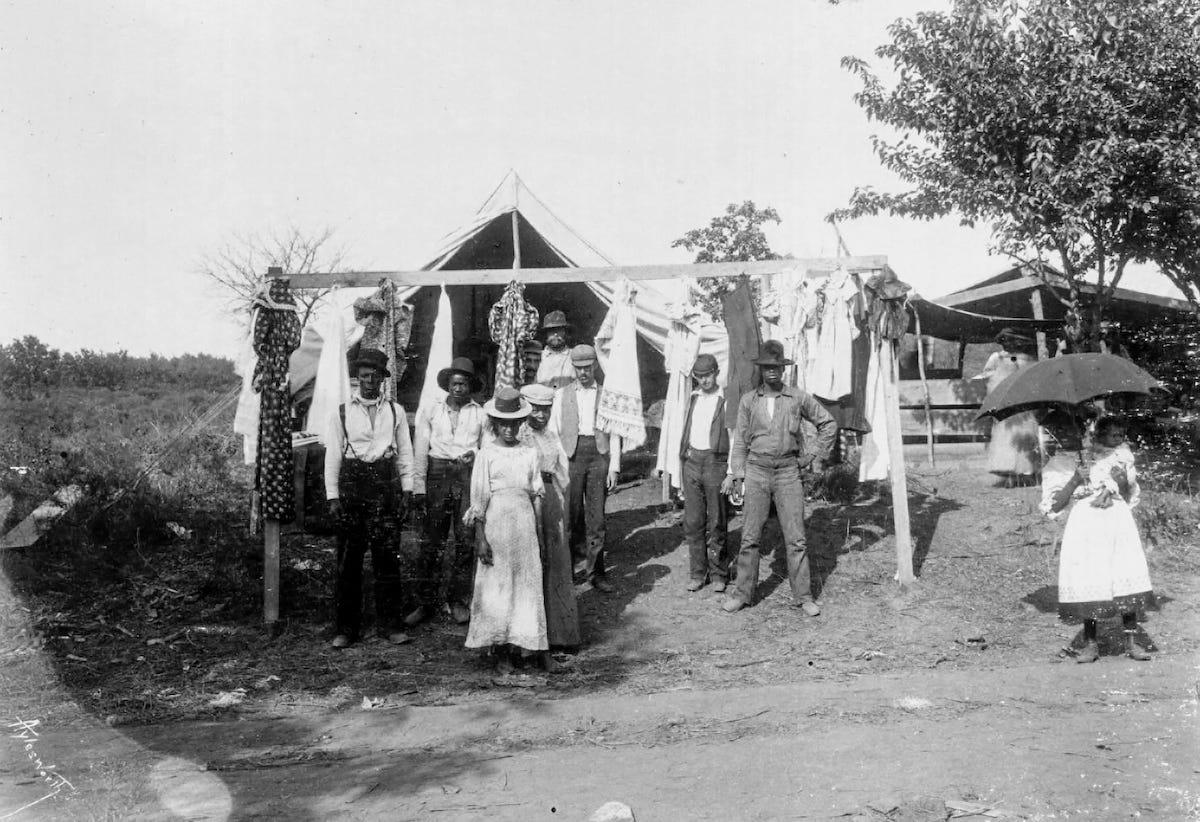

The following year (1902), Joe decided to move his family to free land in Oklahoma’s new settlement of the “land of the five civilized tribes.” They started out as part of a wagon train heading north toward what Joe heard were newly established black settlements within the territory.

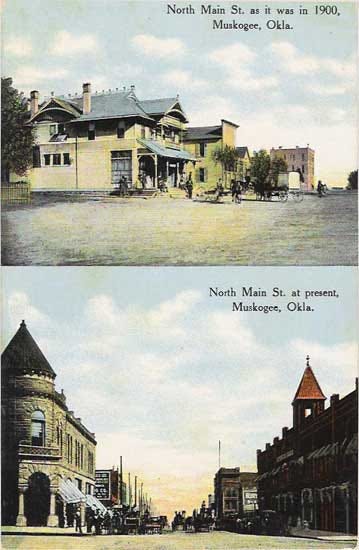

The family settled in Muskogee, the second largest town in the area. It was also a town with a heavy Black population of successful businesses and farms. The family purchased a plot of land big enough to build a house and several others for the relatives who soon followed them. Within the year they mapped out rows of vegetables and fruits, filled coops with chickens, and kept several dairy cows. Grandfather Allen traveled up from Waco in the fall to butcher the autumn hogs for winter storage.

Joe oversaw another white family’s dairy farm and served as their houseman. Maggie cooked for them on special occasions when her own family’s duties permitted. From a young age, Cleora was brought along to help her mother when the family entertained and where she began to learn the serving skills required for high-class social events.

At 22, Cleora was invited by an aunt to come live with her in Tulsa because the neighbor of the family she worked for needed a maid. Her parents were reluctant to give their permission. “There was some concern because of the racial disturbances in Tulsa two years earlier.” But since the 1921 Tulsa race massacre, the destroyed neighborhood of Greenwood had been miraculously rebuilt and was once again thriving.

For the next 20 years, Cleora was employed as the cook for a succession of affluent oil families. Her most prominent employers were Mr. and Mrs. George W. Snedden, whose wealth stemmed from several oil fields around the state and survived the Depression. Her cooking repertoire increased to include fancy cocktail hour affairs (“liquor flowed like black gold for those who could afford it”) and dishes her employers discovered in their yearly overseas travels.

Cleora left the Sneddens after she married George Butler in 1940; he didn’t care for her working for them. Sometimes, though, Mrs. Snedden hired her to cater large parties such as her daughter’s society debut and wedding. She also picked up occasional work in other wealthy households where she was given more room to create dishes, such as a graham cracker torte that went on to be a Tulsa favorite.

Cleora didn’t cook much throughout the 1950s. Instead, she took care of her father-in-law and helped her husband, who was showing the first signs of diabetes. In her restlessness, though, she began to make hats. This was after a very exclusive shop prohibited her from trying hats on unless she went into the back room. So enraged, she nevertheless bought two expensive hats then told the saleswoman she’d never shop there again. Cleora went home and found a correspondence course in millinery to learn how to make her own. She got so good that she never bought another hat and sold many of them for $50 apiece.

After her father-in-law’s death, she took a stock clerk job at Nan Pendleton, one of the most expensive dress shops in Tulsa. Through its owner, Maybelle Lauder, she met many rich women and, with her reputation as a fine cook remembered from her years working in private homes, Cleora began to freelance on her off hours. She soon grew so busy and confident in her business acumen that she felt she could set out on her own. In 1962, she and George opened Cleora’s Pastry Shop and Catering on a street just outside the boundaries of Greenwood. She took care of the pies and cakes. He made the donuts.

The shop was an immediate hit on both sides of the counter. People came from out of town to buy her sourdough bread, and institutions such as the Tulsa Opera Guild and Philharmonic hired her for their benefit dinners and celebrity celebrations.

One of the shop’s biggest fans, though, were the construction workers building a new highway a few blocks away. Their luncheon order for the shop’s chili and hamburgers often brought in an additional $500 to $800 a week.

George’s diabetes worsened to the point where he could no longer stand all day, so in 1967 they closed the shop. By this time, the nearby highway was on its way to tearing through Greenwood and proved to be a more destructive force to the community than the riots had been. The shop would have stood in the highway’s path.

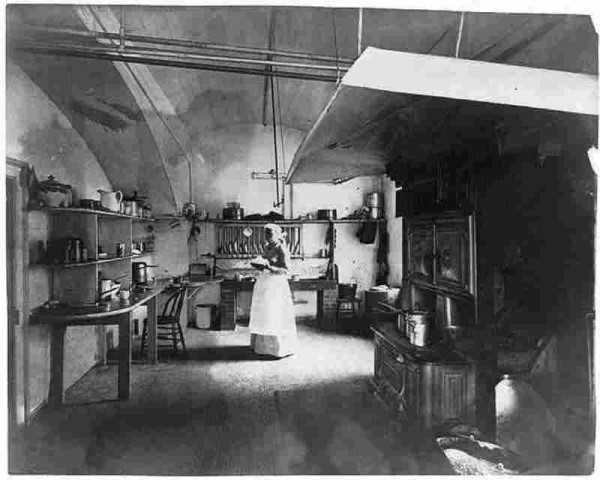

George died in 1970. Cleora filled her time by baking sweet rolls for the students and faculty at a local high school and donated a few hours of her skills at the Episcopal church on the other side of the highway. “Little by little I reestablished my catering business, remodeling the kitchen to accommodate the increasing activity,” she wrote.

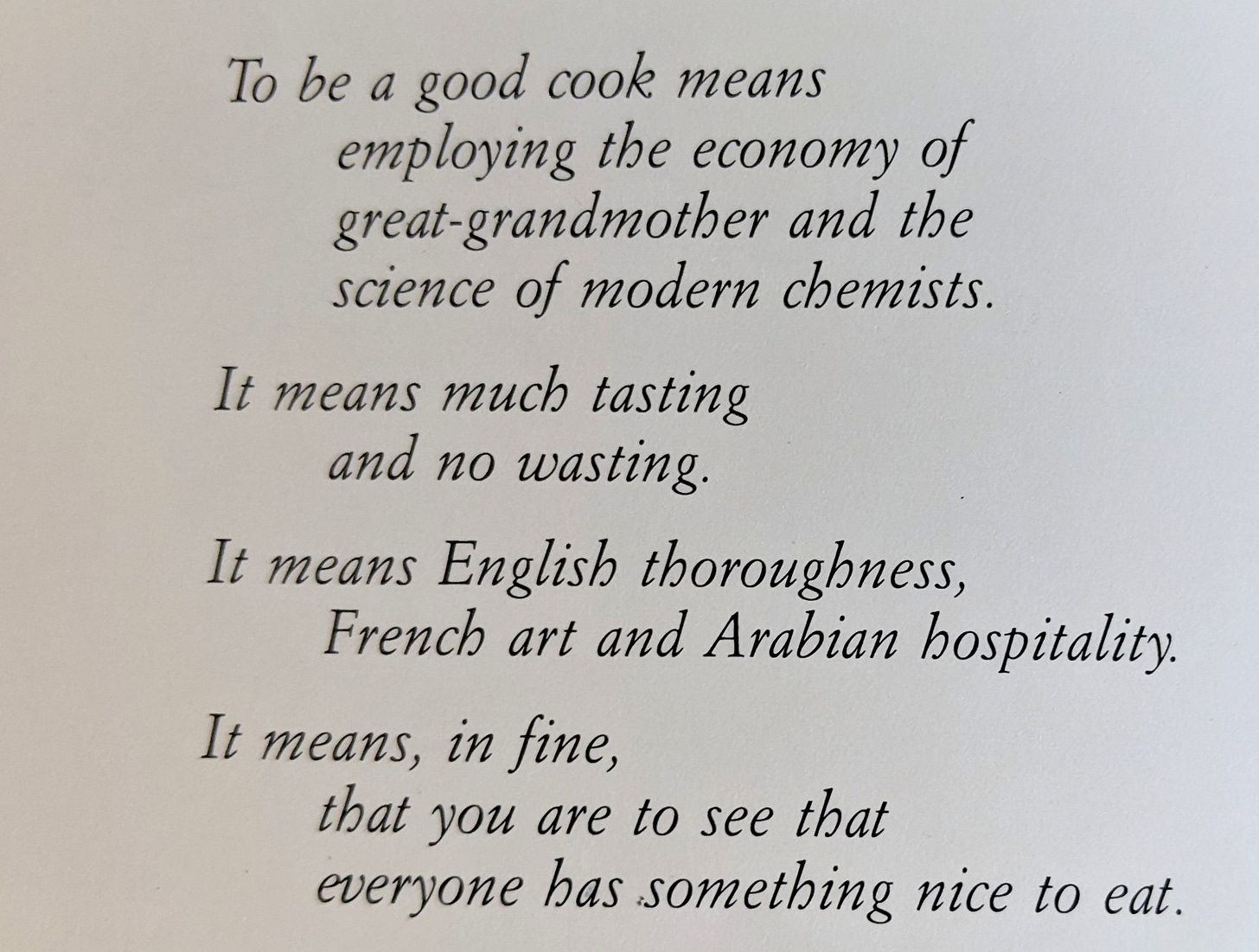

As she approached her 80s, Cleora’s nephew urged her to begin writing down her recipes and stories about her life. With his help—a fine cook, himself, she noted—she gathered together her family’s dishes and those she had learned over the previous 70 years. She ended the manuscript with a poem by John Ruskin that she felt perfectly explained her cooking philosophy.

Cleora died in 1985, a few months after she completed her book.

I’m putting together a small compendium of Cleora’s recipes that takes you from a childhood memory of her mother’s chow-chow to her final recipe, a simple but elegant macadamia chess pie. It’ll be available on Saturday so come on back to get a further sense of how her cooking evolved over the course of eighty years.