I’m so glad you found your way to today’s story. Sign up for a free subscription so you won’t miss the recipe that goes with it on Saturday!

Ms. Johana’s garden is a mess. The summer rains spurred rampant growth and kept her from taming the beds. All of the gardens in East New York resemble hers, even the ones with a large membership. And then there’s COVID. The underserved neighborhood has had among the highest rates of infection and the lowest rates of vaccination. Ms. Johana isn’t vaccinated. She says she won’t chance it because she’s had too many bad reactions to regular vaccines. Instead, she relies on knowing how to take good care of herself.

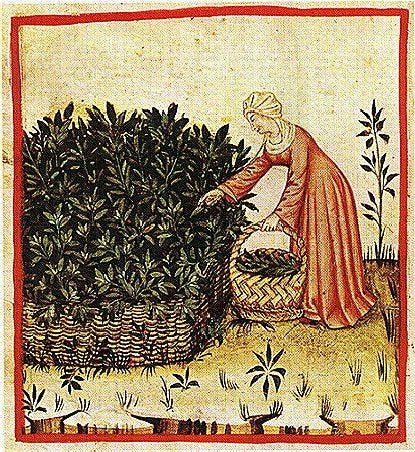

That’s why her garden contains so many herbs. She first planted it with varieties she came to know through her voracious reading of complicatedly plotted historical and fantasy fiction. She prefers stories that take place in medieval times with dragons, complicated battles, and massive skullduggery among the royals. This is why when you walk through her garden she will stop and tell you how to tend to sword wounds, a case of royal gout, mysterious fevers, even the ingredients to mend a broken heart. She also grows a small patch of hops that helps to attract pollinating bees and, according to a neighbor who brews it, an intoxicating beverage that taste close to mead.

The weather will be clear this week so we’re out harvesting the beds. She’ll dry them in her kitchen. Others will be steeped in water, wine, or rum. I’m in charge of the shears while she carries a mesh bag and leads a winding path through the brush.

Sage was the first herb Ms. Johana planted. That was over 20 years ago, and by now it has jumped the borders of its box and spread across the surrounding paths. Make it into a tea to treat fever headache. It also helps with old bones and their constant aches. For that, you soak the leaves in a little brandy and sip from time to time at night.

But what sage is really good for is for healing wounds. Ms. Johana picks three broad leaves and spreads them across her palm. “You take theses and wet them a little, then lay them neatly over your wound. Make sure the entire wound is covered. Back when they had jousting matches, they’d pack a bunch in the wound to stop the bleeding.”

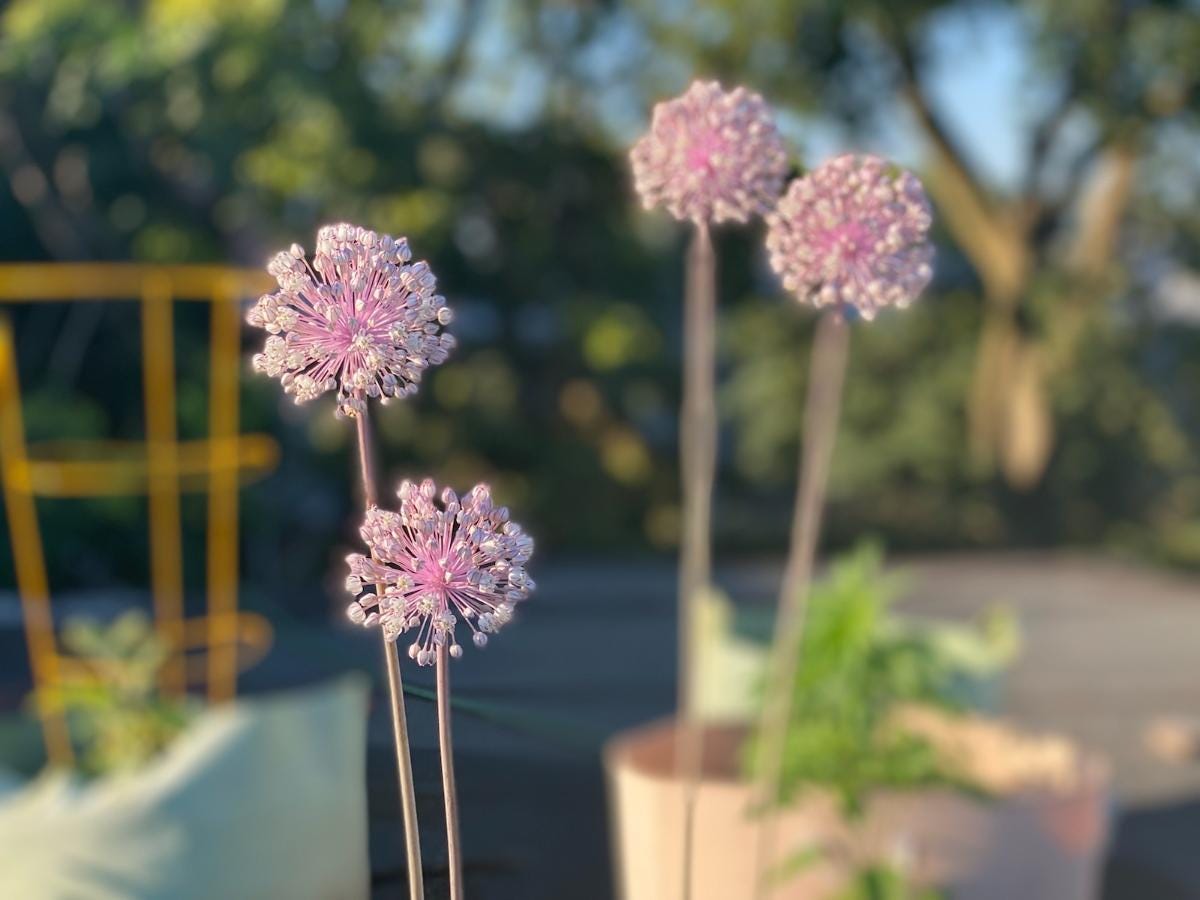

Scooting along the path, Ms. Johana finds Egyptian onions in full bloom behind her lilac bush. The bulb is about the size of a pearl onion, and striped purple, sweeter tasting but intensely pungent. An eye treatment concocted first for Egyptian pharaohs and the spread across Europe by the crusaders consists of pounding the bulb into a thin membrane and laying it across the eye. Ms. Johanna believes—but can’t prove—it’s still very effective.

“You know what this is?” she asks but doesn’t wait for an answer. “Mullein. It comes from the Greek gods and the Greeks carried the whole plant with them whenever they went off fighting somebody.”

She doesn’t tell me why, but I look it up later and it turns out the herb was thought to cure nearly every ailment imaginable that plagued the body, starting at the top (headaches) to the base (hemorrhoids and sore feet).

But her favorites, the two herbs she’s cherished and propagated and watches over almost as bad as a helicopter mother, is borage and St. John’s wort. She found them mentioned in all her books, especially a few spun from the War of the Roses. She also prizes them for how they sit up in their beds, their beautiful flowers a particular favorite among bees. Medieval physicians instructed that when borage is boiled a little in water, then poured into glass bottles and left to sit for a year until it tastes something close to wine it will mend the love sick. Borage was also relied on to treat mental fatigue. If you know anything about life during the Middle Ages, let alone the difficulties brought on by the War of the Roses, you may begin to understand why doctors would be eager to try anything to alleviate their patients’ suffering.

Borage, though, is not a cure. I mention to Ms. Johana that St. John’s wort is still thought of as a possible treatment for depression.

“I don’t know about that. But I do know knights drank it to strengthen their courage before going into battle.”

“Did it work?”

“Why wouldn’t it?”

Ms. Johana doesn’t mention if any of her herbs treated the Black Plague but then maybe her books don’t dwell on those years. I happen to know one, recorded by Elizabeth, Countess of Kent, that she could easily cultivate:

Gather a good measure of milk thistle, yellow dock, thyme, burdock root, chicory root, nettle leaves, violet leaves and flowers, mint, mustard greens, and chickweed. Cover with wine [apple cider] and let sit for three days. Vapor [cook] over a fire until boiling, then press all together and strain through a fine cloth. Add your best honey.

Just incase she decided it’d work as well as the vaccine I keep that recipe for myself.

Stories about Ms. Johana and her East New York garden include one for berries, remanences of East New York, and how we met.

Thank you for reading America Eats! Your support helps me write stories not often told—and celebrate people who should be remembered and acclaimed—in the food world and at the American table.