Virginia Woolf famously proclaimed that it was a woman’s right to have a room of her own. What a ridiculous notion this was (is), not only to allow a woman private time to accomplish something obviously so absurd but also physically impossible, given the size and layout of domestic dwellings that all but the rich could afford. There was only one room that could serve a creative woman’s needs, a room that was already deemed her singular territory. That would be the kitchen.

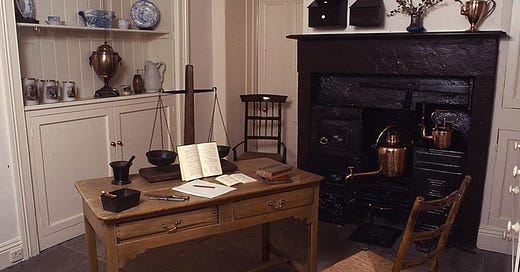

This is Emily Brontë’s kitchen. Paced off by a size 8 shoe, it measures around 9’ x 10’. It is tucked in the back of the house beside the outside door. I don’t remember if there is a window in it (visitors were steadily shooed along) but, if there is, it would look out on a walled yard (the Brontës don’t seem to have been interested in gardening) and the moors. As a child, Emily and her five siblings raced about in it so much that the household’s servant and their aunt would throw them outside no matter what the weather. The kitchen came into Emily’s sole possession when her aunt died and the servant injured her leg. She was grateful for the excuse to leave Brussels where she was supposed to be preparing with her sister Charlotte to become a governess. She was twenty-four years old with a tower of poems in her pocket, many portraying an elaborate fantasy world that, in scope and inventive brutality, rival Game of Thrones. She assumed responsibility for the house, with the kitchen strictly under her domain.

The people with me seemed shocked upon learning how good a cook Emily was. Her bread was recorded as being particularly fine. Given the rhythm of a large family’s daily meals—from breakfast to evening tea, with the needs of frequent guests in-between—she would have had to bake several loaves each morning. It could be strange to contemplate her happily accepting what should have been a hindrance to accomplishing what was most indispensable to her being. Especially in this kitchen with an oven that required constant attention and a small table serving as the lone countertop where a tall woman (for her time) would spend considerable back-aching hours bent over to knead and chop and stir. At the end of the day, Emily surely was too weary to do much more than go to bed.

But in the kitchen she was alone for much of the time. Like the best of studies, the kitchen provided her with a modicum of extensive solitude. Wuthering Heights was conceived and written in a year while she tended the stove. Hundreds of poems were composed while pots were brought to boil and the oven fires kept alive. Where else in a crowded house would she have had long stretches of uninterrupted time to contemplate the intricacies of a masterpiece?

An incomplete gathering of other women writers' kitchen work: Jane Austen’s Brown Butter Bread Pudding Tarts Sylvia Plath’s Lemon Pudding Cakes Willa Cather’s Spiced Plum Kolache Emily Dickenson's Black Cake A ton of Joan Didion's favorite recipes

Emily Brontë’s Recipe for Maslin Bread

Actually, it isn’t hers. If Brontë wrote down recipes they have, like much of her literary output, not survived. But maslin bread is the historical Yorkshire bread most commonly eaten in her lifetime. There are a host of recipes I could have chosen but I settled for the one presented by the great English food writer, Elizabeth David****! She was a stickler for accuracy and, since I am not a bread baker, I am presenting it as she recorded it.

(****! David has kind of fallen off the popular radar. Personally speaking, she deserves to be honored along side, or even above, her near-contempory, M.F.K. Fisher—yep, I said that. I’m working on a piece about her now so we can argue the point later!)

6 ounces stoneground rye flour 4 ounces stoneground wholemeal flour 10 ounces stoneground barley flour 1 1/2 cups lukewarm water 1 teaspoon dried yeast (or 1 ounce) fresh yeast [see note below] 2 teaspoon salt Preheat oven 250 degrees. Pour the water into a bowl and sprinkle the yeast on top. Stir well and leave it to activate a little. Put all the flours and salt into a large bowl and mix them well together. Add the water and activated yeast to the flours and with your hand gently bring the ingredients together to form a dough. Tip the dough onto a lightly floured surface, and knead the dough, pushing with the heel of your hand, then folding it over on itself. It will be quite sticky at first, but gradually it will begin to loose its sticky feel. Knead the dough for at least 10 minutes. Place the ball of dough in a greased bowl, and cover. Leave it to rest for around an hour. Turn the dough out onto a lightly floured surface and knead again, forming it into a ball. It should feel less sticky than before. Place the dough into a well-greased circular cooking container and cover with a damp tea towel. Leave it to rise again in a warm spot until it's almost double in size. Turn the dough out on a very lightly dusted counter and lightly punch down once, then place in a bread pan. Place in the oven and bake for around 10 minutes. Adjust the oven temperature to 200 degrees and bake for 15 minutes more. The bread is finished when the top is firm to the touch and nicely brown. If you're still unsure, tap its base. If you hear a hollow sound, it's done. Turn the bread out onto a rack and completely cool before slicing. Note: Emily would have used a sourdough starter. If you have one around, adjust the quanity for the recipe and use it.

Thank you all for stopping by today! Hope to see you back here next Tuesday. ~Pat

Right? And, yes, Jane! They're stuck in the English food is (was) bad lane.

Lovely piece!