Bulow Plantation is one of Florida’s better-known historical landmarks that your GPS assures you is right off the Old Kings Road. If it is, you keep missing it. The third time down the road you turn into the Bulow RV Resort, thinking it has to be nearby or at least there will be someone to ask for help. You find the resort’s office next to the tiny swimming pool packed with happy-looking retirees, and the nice woman behind thick plexiglass directs you to turn left as soon as you pull out of its parking lot. That’s what you do and immediately find yourself having to trust that this dirt lane, bordered on each side by impenetrable groves of forest, is not a cow path.

At least seven minutes pass before a clearing appears up ahead. Here you are at last, in the middle of the remains of the Bulow Plantation, once the largest producer of sugarcane in the early years of the 19th century.

A short history of the plantation: In 1821, Charles Bulow brought 300 of his slaves down from his family’s plantation in Charleston, South Carolina, to this wild part of the country with the purpose of establishing a profitable sugarcane business. Sugar was in huge demand around the world, and the French, Spanish, and English colonists in the Caribbean were making a fortune. The American South held all the ingredients to match the islands—fertile soil, an agreeable climate, and an abundant supply of slaves.

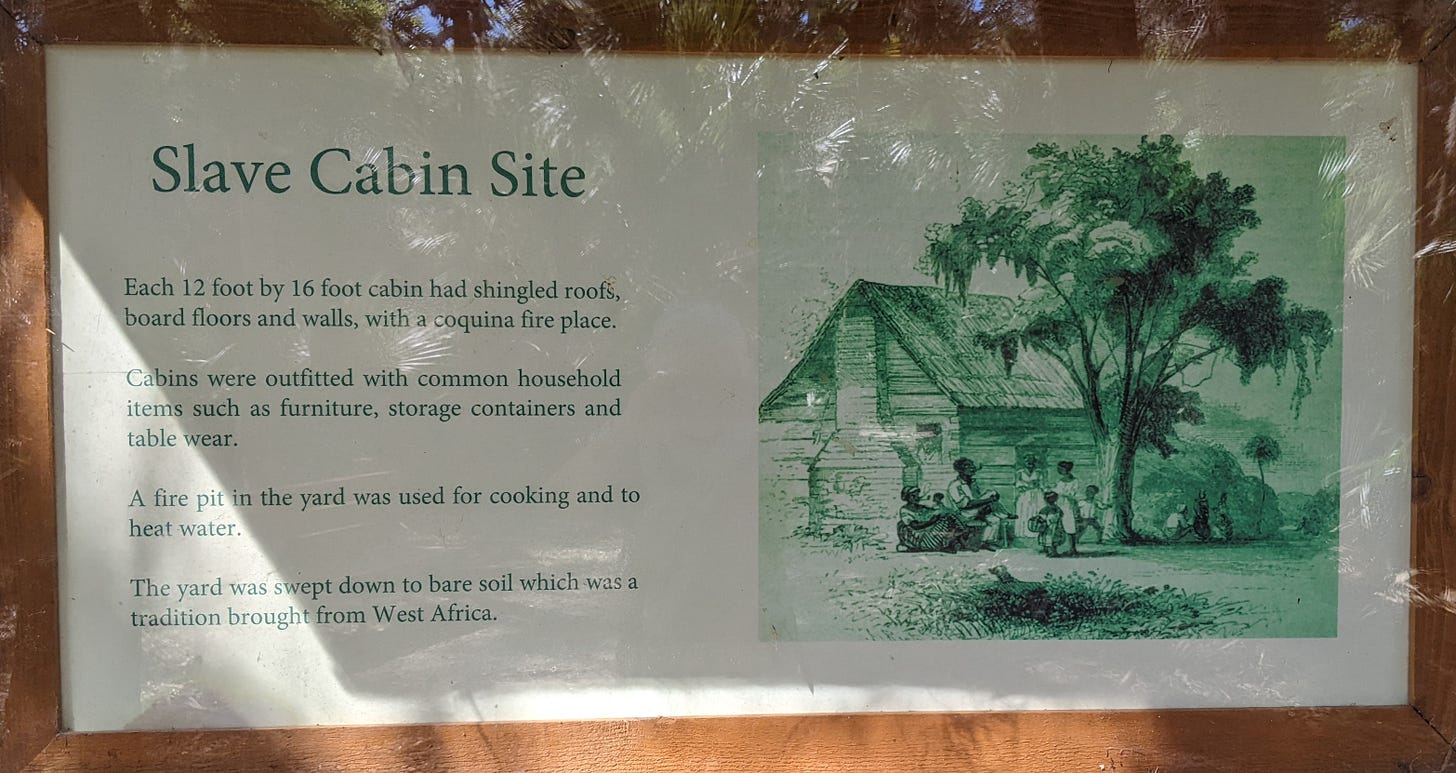

Bulow bought 4,675 acres along a tidal basin that gave a direct route to coastal ports. His slaves hacked out 2,150 acres. The majority of the plots would be for cane and the rest for insurance crops—rice, indigo, and cotton. The slaves also built a home for Charles, cabins for themselves, and several outer structures for horses and farm animals, grain, and equipment storage. A large sugar mill constructed from stone cut in the nearby coquina quarry was situated a mile or two away from the main house. The plantation had yet to be completed when Charles died two years later, some records attributing it to yellow fever, given the surrounding mosquito-infested marshlands.

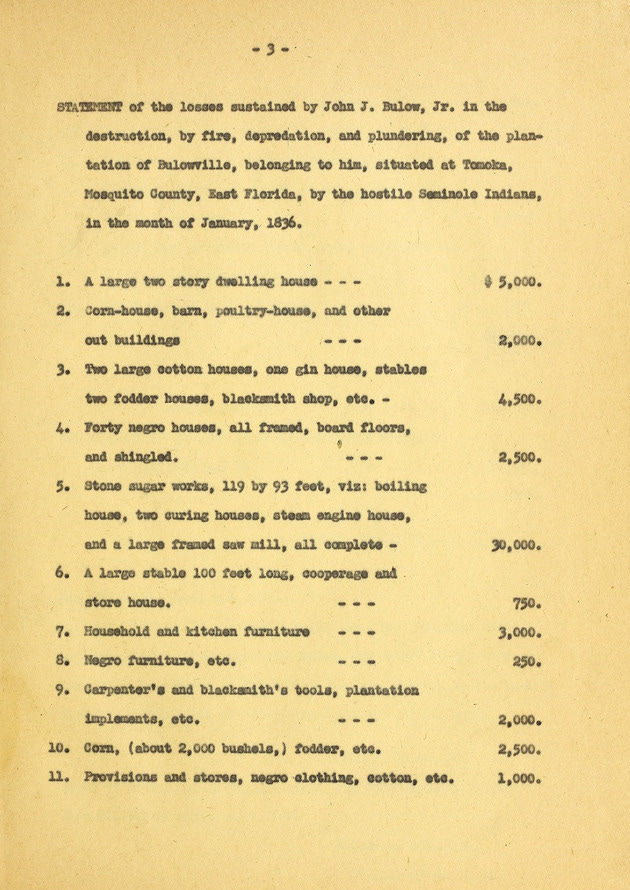

His teenage son, John, was summoned from his Paris school. Smart and ambitious, and with the help of an experienced foreman, he further expanded the plantation, buying another hundred or so slaves to help increase sugar production. All went well until the Second Seminole War. On January 11, 1836, the Seminoles burnt the entire plantation and its crops to the ground. John retreated to the family’s St. Augustine townhouse. His slaves were housed in a squalor camp on a nearby island where other plantation owners had sequestered their slaves during the crisis. John petitioned the government to provide restitution, but he died months later at the age of 26. There is no record about what caused his death (a broken heart was one speculation). Nothing is known about what happened to the Bulows’ slaves.

The ruins of the Bulow Plantation are maintained by the Florida State Parks Department. They cleared a path through the forest that swallowed the plantation after it was abandoned. The path winds from one ruin to the next: Pass the traces of the mansion, to the vast scorched sugar mill complex, and over to the Bulow’s spring house.

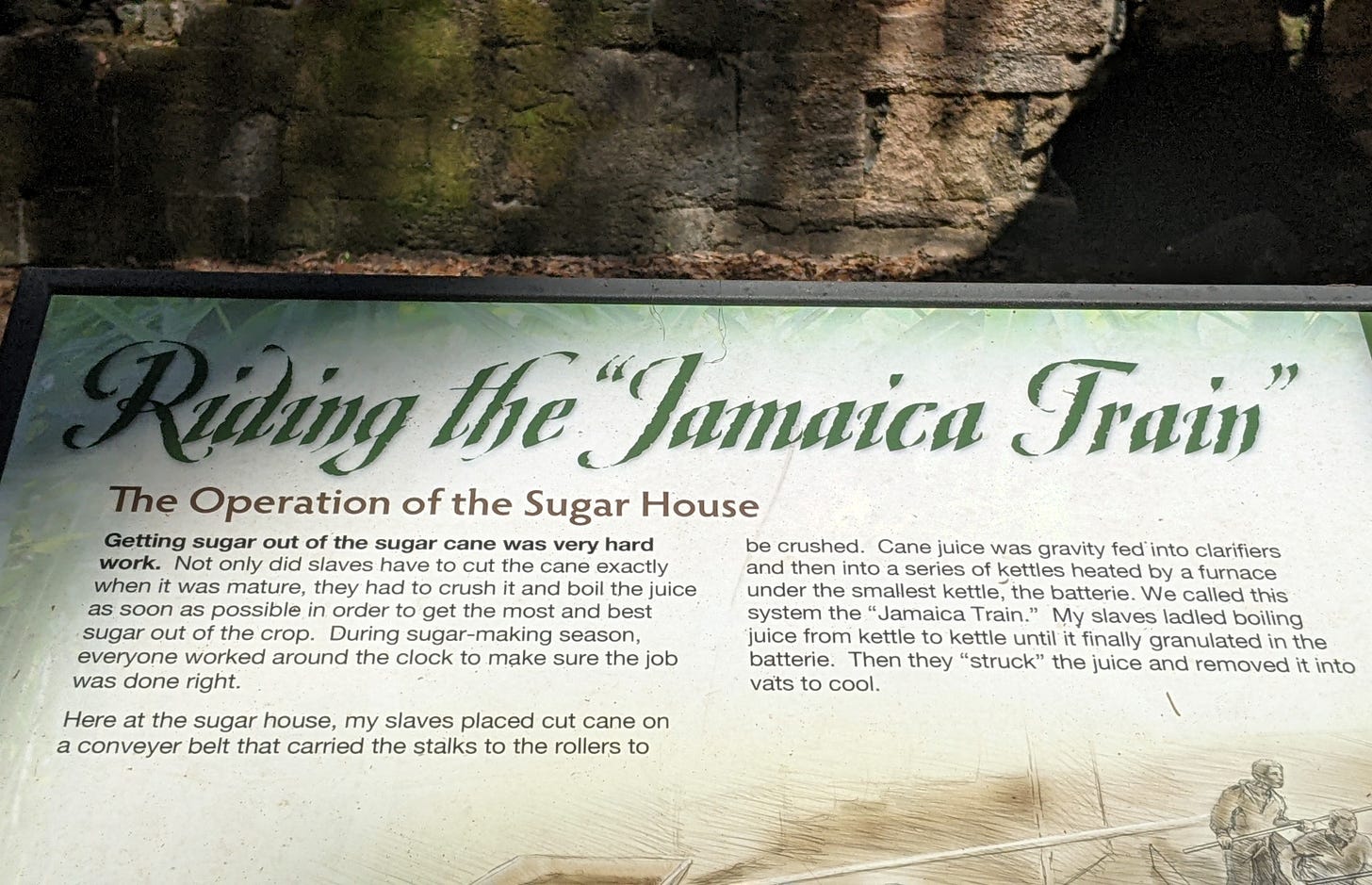

Along the way are illustrated signs, written from John Bulow’s point of view. The text gives precise information about processing the cane. Bulow’s slaves tended to about 1,000 acres of cane and produced 2,000 barrels of sugar each year.

John also gives some hints about his life as a very social young man in his early twenties, possessed of enormous wealth, a fine Paris education, a commodious house stocked with the best wine, and a library full of novels. He fished and hunted and, according to accounts from his contemporaries, became quite famous for lavish parties and hosting famous guests.

Every now and then there are hints of how his slaves lived and were treated.

Finally, you come to where the slave cabins once stood. They are all gone, but the footprint of one is marked with four erect 4’x4’s and measures 12’ x 16,’ about the size of a modern tiny house.

Afterwards, you’re back in the parking lot where you find a picnic table to sit for a spell and try to take in everything you’ve learned about the Bulow Plantation. What nags you is what you didn’t learn, specifically the brutality of the sugar industry. No other crop tended by slaves was as deadly. You can’t help but wonder if the plantation’s well-maintained path cuts through a burial ground.

The production of sugar required – and killed – hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans. So, between 1748 and 1788 over 1,200 ships brought over 335,000 enslaved Africans to Jamaica, Britain’s largest sugar-producing colony. Yet in 1788 a Jamaican census recorded that only 226,432 enslaved men, women and children were alive on the island. Even with all who had already been there before 1748, the more than 335,000 new arrivals, and all of the children born to enslaved mothers, many died to produce sugar.—from Enslaved People’s Work on Sugar Plantations

It’s the quiet that gets you most, how lacking in the thwacking sound of the harvest, the mill’s machinery rhythmic smashing of the stalks and its chimneys spewing thick sugary acidic smoke. Above all, what’s missing is the din of human voices that these acres once contained.

Is it unfair to want these elements incorporated into the story told at the Bulow Plantation? To elaborate on the signs’ few sentences currently given over to John Bulow’s slaves? To use this place as an opportunity to explore the continuing personal and ecological cost of producing foodstuffs?

But then you realize that you live in a period of time when such history is deemed unnecessary, even harmful, especially to the children who are running about the remains of the mansion. You are sitting in a state that just may be the leading champion in the suppression of our country’s legacy and common cause.

Right on cue, two couples slowly walk by.

“It’s such a romantic place, isn’t it?” one of the women says.

You want to reply to her, “It is haunted land.” You don’t, though, not knowing where in such a long history to begin. Instead, you return to your car and drive back up the dirt road. This time, you find the way out without trouble.

Isn't that crazy? People in the north don't know about how much slavery there was up here and how prevalent it was to send runaways back south. All the more reason for places like the plantation to talk about it. And thanks in advance for the link. I'm so appreciative of your support and making me laugh!

This piece is so timely--I'm writing a post on sugar for later this summer, and definitely plan to link back to this! when I lived in FL, I was amazed how few Floridians thought about the legacy of slavery and sugar production in their own backyards.