Give Praise to the Household of Ruth

You will never be half the woman they are.

The wonder that comes over you upon reading the account of the “Annual Household of Ruth Dinner” is that there is so much gracious benevolence in the world. You can’t imagine giving it yourself in the same circumstances. But there it is in a slim story about a dinner that took place in 1938 in Wilmer, Alabama, a tiny town near the state’s southwestern corner, a spit’s distance away from the Mississippi border.

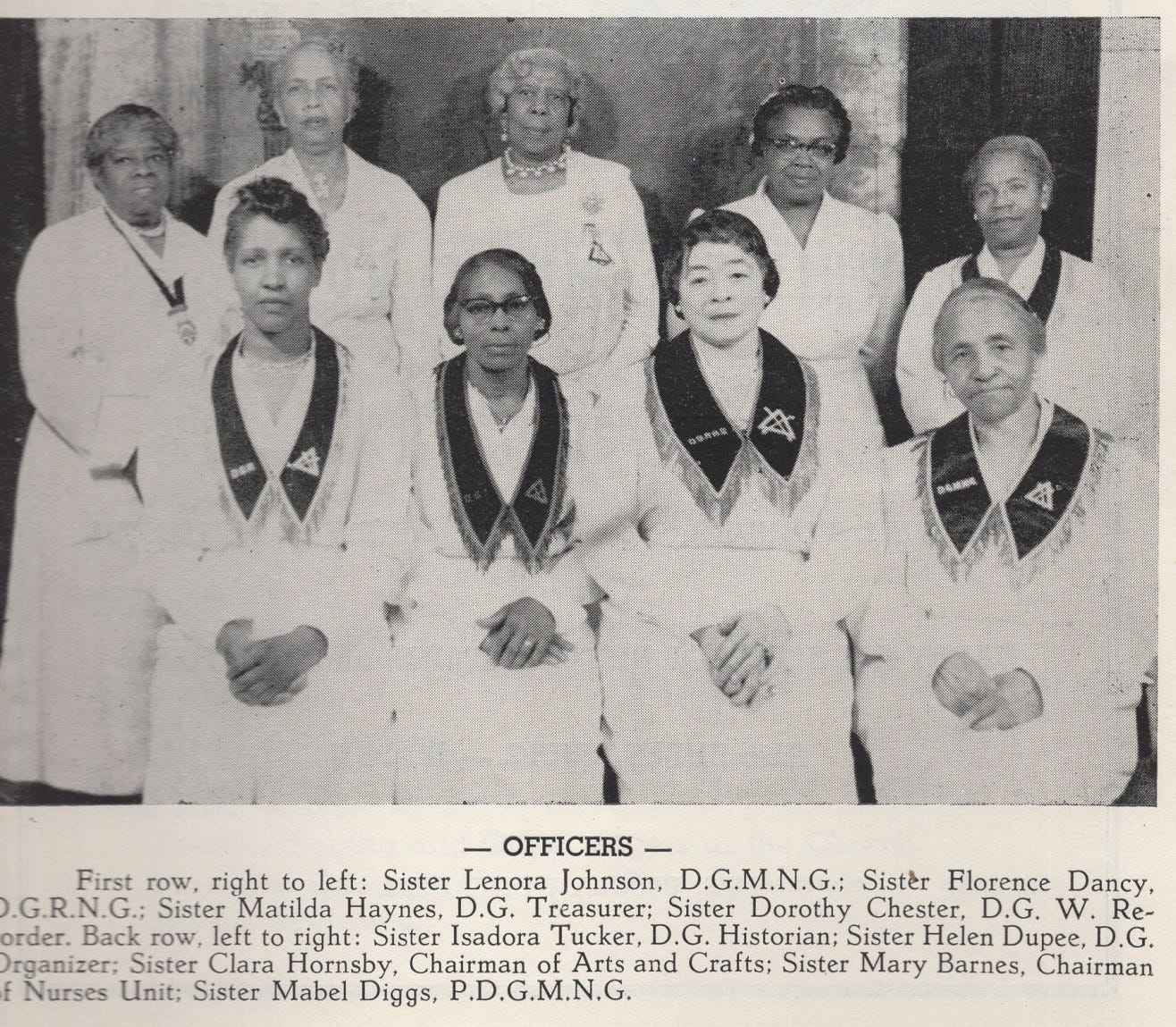

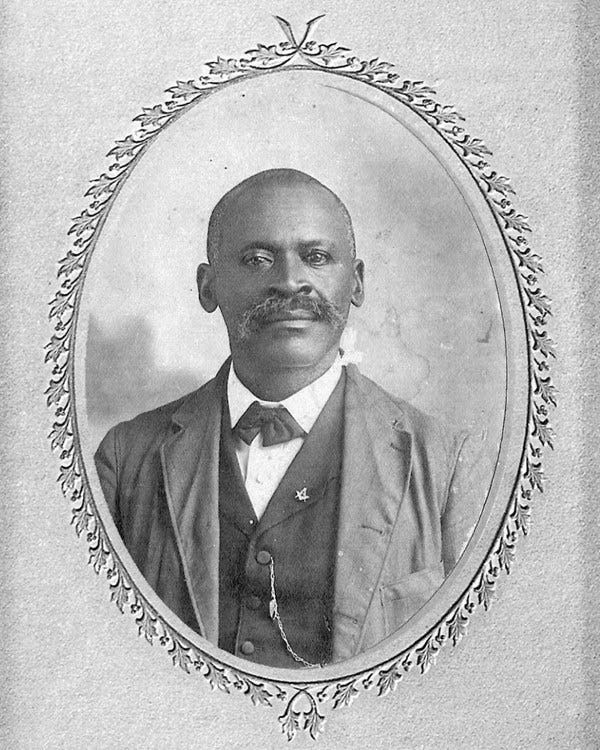

The Household of Ruth is the women section of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, the oldest black philanthropic society in the country. The Order was established in 1849 by Peter Ogden, a free black who worked as a ship steward and who became familiar with the good works of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows during the periods when his ship docked in England. The American Odd Fellows wouldn’t allow a black man into their ranks so he asked the English branch for help and they gave him special dispensation to form the Grand United Order. The Ruth members have always been independent of the men but they support the Order’s work by organizing outreach events, fund raisers, and, most especially, recruiting members’ female relations who aren’t already in the Household of Ruth. The Grand United Order and the Household of Ruth remain active today in black communities across the country and continue to offer social service programs and assistance with life and business insurance, medical expenses and burial costs.

The story you read was written by Ila Prine as part of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Writers Project manuscript, America Eats!. The dinner she attended sounds like it was pretty fine but what struck you the most was the good will and charity given to the whites in the community, some of whom owned the parents and grandparents of the organization’s members. Many still lived with their former masters' last names.

You can’t imagine how it would be possible to share a table with those who enslaved you. But then they have a faith you don’t have nor a community that’s seen you through hundreds of years of brutality. This is what you try to understand while reading Prine’s story.

(A word about the following text: It is reproduced as it was written in 1938. It reflects the language and terms used at the time which may be found offensive today. The images have been added for this story.)

Annual Household of Ruth Dinner

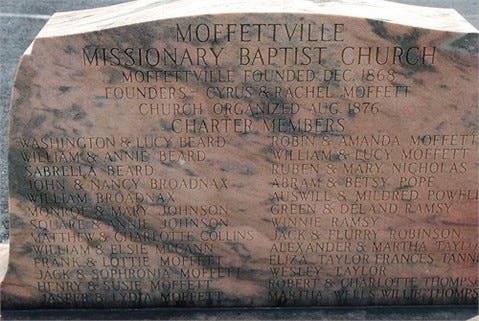

by Ila B. Prine of the Mobile, Alabama office of the Federal Writers ProgramThree miles north of Wilmer, Alabama is a scattered community that was first settled by the slaves of the Bob Moffatt family. Mr. Moffatt was a large cattle owner and farmer, who lived near the Mississippi state line, in the extreme western part of Mobile County. The old family burying ground is on what is commonly called Dog River, but the true name is the Escatawpoa River.

Among these slaves was a Negro woman named Rachael Moffatt, who rescued Mrs. Mary Moffatt, her mistress, from her burning home, after the house had been robbed and fired by the notorious Copeland gang, who once roamed this section of the Gulf Coast, robbing and burning as they went. Shortly before this robbery Mr. Moffatt had sold a herd of cattle. The gang knew this, went to his home while he was away, and tried to force Mrs. Moffatt to tell where the money was hidden. The money had been sewed in a mattress, but she refused to tell the hiding place, so the robbers tied her up, and set fire to the house. The Negro slaves were unable to save the house, but Rachael rushed in and dragged Mrs. Moffatt and the mattress in which the money was hidden, from the burning structure.

“Granny” Rachael, as she was known in the later part of her life, was one of the first settlers of this Negro community. She lived to be 104 years old. Among the settlers was “Uncle Billy” Broadnax, who lived to be 109 years old. He remembered the stars falling. [This refers to the Confederate flag.]

This entire community is made up of the Negro descendants of the Moffatts and Broadnaxs. There are only a few of the older generation left, and their eyes are growing dim, their hair white, and their steps are slow and feeble. Among the older ones living today are “Uncle John” Broadnax and “Uncle Will” Beard.

No white person has ever lived in the community, and it is one of the most peaceful and quiet settlements to be found anywhere in the country. The people are peace-loving and deeply religious. Two of the main buildings in the scattered community are the Baptist Church and the “Household of Ruth Lodge” building.

On the second Sunday in May of each year, the Household of Ruth has its annual meeting and dinner. To most of the people in the community it is the big “turn-out.” Both Negroes and white people attend this turn-out, and there is always a place reserved for the white people in the church, as well as at the dinner table.

The services start at 10 A.M. when all members of the Household of Ruth meet at the lodge building and march in pairs to the church. When they reach the church they march into the building up one side and down the other, and then out again, singing “Onward Christian Soldiers.” They repeat the procedure, and the second time they enter the church they remain standing, lifting both hands three times and giving a clap after the third time. Then the leader raps the gavel and they are seated. After this, the preacher begins his sermon.

In former years the members of this order wore black skirts, white waists, white sailor hats, and white gloves. When one of their members die, they go in a group, all dressed in black with a black bow pinned across the front of the waist. The members then wear the black bow for thirty days as an emblem of mourning. In recent years they have changed their uniform to blue dresses, with white collar and cuffs, white hats and gloves.

After the morning services, dinner is spread on a long table, which is covered with snow-white clothes. The dinner consists of fried chicken, baked beef, roast kid, and sometimes chicken, stewed with rice or dumplings. Light bread, cakes, pies, potato salad and home made pickles are also served. The bread is laid along the edge of the table, and it usually serves as a platter to put salad on, or to hold the stew or fried chicken. The men make coffee in a large clean zinc bucket.

After the dinner is spread, and a certain side arranged for the white people, every one is called to dinner, and the preacher, or some prominent white man, is asked to return thanks.

In the afternoon the crowds are free to do as they please, but the time is devoted mostly to singing. If there are many white visitors, they are asked to sing, and afterward the people of the community sing. One has never heard the old time darkies sing in their own church, has missed a stirring occasion.

Final note: Today, Moffattville is marked by the cemetery and the baptist church. The Grand United Order of Odd Fellows’ lodge no longer stands.