How to Feed an Entire City

Even more complicated than you imagine

The waterways shared by New York and New Jersey served as one of the nation’s busiest ports of entry almost as soon as the Dutch West India Trading Company navigated its first barges down the Hudson and East rivers in the early 17th century. As native and international merchant and passenger ships proliferated, as piers were added and more warehouses crowded the 1,500 miles of shoreline, the harbor turned into the young country’s first huge traffic jam. By the turn of the 20th century, the intolerable chaos and dangerous conditions for dock and warehouse workers had become untenable. In spring 1921, they threatened to strike.

125,000 marine workers went out on strike. . . .putting half a million other people out of work, tying up 3,600 American ships and paralyzing shipping on both coasts.—Dick Sheridan, Daily News, “History of the Port Authority: When N.Y. and N.J. joined forces to solve chaos at nation's foremost gateway,” August 14, 2017

The strike was adverted by a 25-cent raise and more oversight given to the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. But the risk of one really happening exposed a grave peril to the surrounding population: If the strike had continued or, worse, a catastrophic event such as war blocked the harbor, food shipments would effectively stop and lead to massive starvation in the city.

No one had ever considered what was needed to feed a city with over six million people. How much food would be necessary? What kind of food would prove indispensable for a city composed of many people from other countries and customs? Even the basics were unknown: How many markets, restaurants, hotels, and corner stores were in the metropolitan area? How many owners, workers, and cooks would there be?

(You have to watch this terrific video archived at Getty Images. It shows shoppers on the street above going about their morning marketing.)

The Port Authority and city officials issued reports, but neither went far enough. And so, in 1936, they turned to the city’s office of the Works Progress Administration’s (WPA) Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) and commissioned an exhaustive study that would provide exact quantities, points of origin, and methods of distribution. The city’s office was overstaffed with out-of-work novelists, poets, playwrights, and newspaper reporters, and they went beyond the requested cold facts to include sketches and intimate profiles of people going about their daily life. By 1939, a final draft, called Feeding the City, was ready. The project’s editors realized that the general public would be interested in reading it, and they began to prepare it for publication. But the book never materialized. War was breaking out in Europe, and Congress, in search of money, began to shut down the WPA. Every draft, all the writers’ notes, and the intended photographs for Feeding the City were microfilmed and the spools sent to the city’s Municipal Archive, where they remain today.

Over the years, scholars have scanned through the reels to glean data and facts about the city in the years before World War II. But anyone can go into the archive and pull out the Feeding the City’s reels from a file cabinet. Find a seat at one of the old reading machines. Thread the film through the rollers, adjust the lens to magnify the dark pages that begin to appear on the light screen, and start reading:

Butter: 265,000,000 pounds brought in all year by rails, trucks, and boats predominately from Iowa, Minnesota, and Illinois.

Fish: 160 varieties from all over the world, about 25,000,000 pounds, pass through the Fulton Fish Market during the busy season that runs from early spring to late fall.

Apples: 300,000,000 pounds from wholesale purveyors and upstate and New Jersey farmers brought in by truck and rails to piers 10, 20, and 21 along the Hudson River.

Restaurants: 20,000 across the metropolitan area—9,000 modest, 5,000 luncheonettes, approximately 300 high-end gourmet establishments, and the rest divided into tea rooms, chop houses, and chain restaurants.

The Last Pushcart: a story about the fight that broke out when the police tried to dismantle the last cart on the Lower East Side.

Bakery differences between Italian bakers in Greenwich Village (better wedding cakes) and German bakers on the Upper East Side (better chocolate and pastries).

The Mean Tale of Durable Malloy, a news article about how the Bronx Murder Syndicate tried to kill the unfortunate Malloy in a Bronx speakeasy for his life insurance money. He survived four attempts in one night. Finally his captors got him drunk enough that they could pour gasoline down his throat with a hose attached to a funnel.

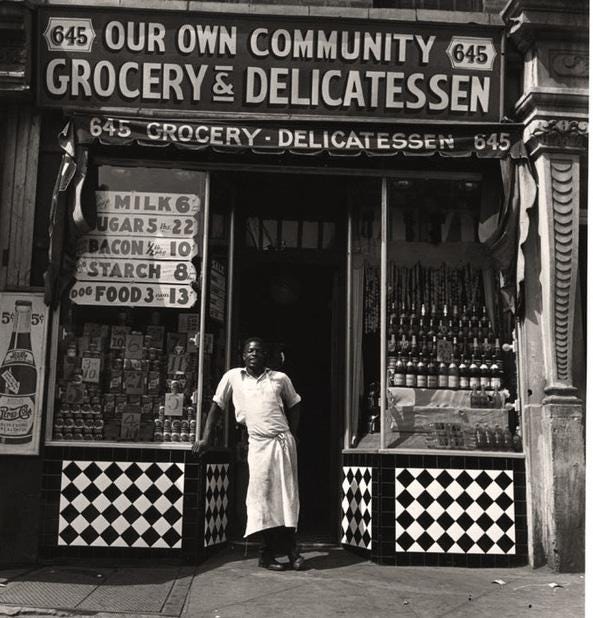

Outside the archives’ long windows is a view of New York City today: food trucks offering dishes from across the globe. The Union Square farmers market is 28 blocks away. Spread across the five boroughs are bodegas and grocery and specialty markets; butchers; and fish, vegetable, wine, and liquor stores. Restaurants and bars are on every street corner.

Eighty-two years after the federal writers composed Feeding the City, what would it take to feed the 18,823,000 people currently living in the New York City area? Nobody knows.

what an ambitious forecast!

Fascinating!