I Hate St. Patrick's Day

It's a complicated immigrant story.

My Irish roots are irrefutable. My mom’s parents came to America from Donegal; my dad’s grandfather, too. My parish church was built by Irish immigrants, and Michael Davitt’s mother is buried in its churchyard. St. Patrick’s Day was a huge religious and community event for us. There was a small parade in our neighborhood. Often, especially when the family’s adults and my parents’ friends were young, there was a gathering at someone’s home or the Irish Club. Jameson replaced the cheap stuff; corned beef and cabbage boiled on the stove and soda bread baked in the oven. The day meant traditional and rebel songs on the stereo and oft-told stories exaggerated into legends. It meant being swaddled in an ancient cloth of belonging.

That all changed when I came to live in New York City, and the day turned into a navigational feat through the Irish-for-the-day pretenders, among whom there were surely a few British. By lunch, and especially after work, this required drawing a detailed route that might possibly avoid roaming bands of insanely blotto men who felt it their due to grab a young woman who happened to have a face right out of Ireland. Arms hooked around me, bolder ones backed me into the side of a building where they leaned their bodies hard against me to take their Irish good luck kiss. This, in broad daylight, in the middle of the city, without a single soul seeming to think the struggling woman might not be having as much fun as everyone else. It was a fine hallelujah day when I was deemed to have aged out of desirability and freed of such shenanigans.

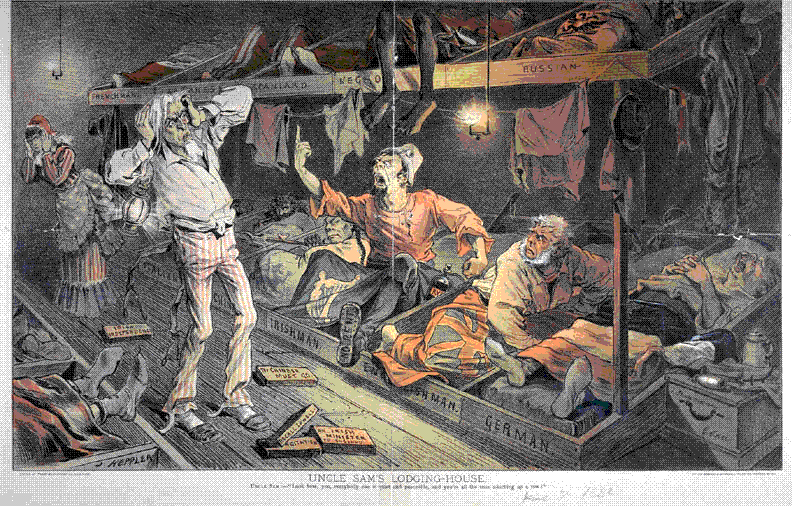

The physical abuse and the day’s license for drunken mayhem pretty much destroyed any joy and pride I take in St. Patrick’s Day. What’s increasingly dishonored is the day’s history as a protest against the ethnic and religious intolerance after the massive influx of Irish during the potato famine.

A wholly new political party, the Know-Nothings, formed with the single objective to defend the country’s white Protestant majority against them and other immigrant groups from Europe, as well as China, very often by inciting bloody violence against them. Go ahead and see parallels to the current Republican party and far-right militaristic groups in the history of the Know-Nothings. Only through the Civil War and the vast enlistment of immigrants, especially the Irish (who were poorer and stood the most to gain by becoming soldiers), did they begin to gain a foothold of acceptance in America.

I know this is a bit of a party-pooper griping story, but there it is. Many friends of Irish descent and my brother and sister feel the same. Come St. Patrick Day, we may meet in a bar for a drink or wander down to our neighborhood’s small parade but then go back home and have a quiet day.

Now comes a twist that I’m forced to report: I just did some fact-checking with my son, who reminded me about the blow-out St. Patrick’s Day parties he threw in our basement when he was young. The majority of his friends are Irish, and the beer and whiskey flowed. I admitted to him that PTSD has blocked out this period, as happens with some parents after their children’s wild years. Then again, I also fact-checked with my brother, who verifies that the day is known as amateur Irish day and best kept among our family and friends.

Still….My parents’ generation is dead, and that gives the day a mournful tone: My brother has gone to the cemetery and poured our dad a Guinness. I’ve already pulled out my grandmother’s soda bread recipe and, come Thursday, will serve corned beef and cabbage.

It is a very complicated day, as an immigrant’s history and heritage always is.

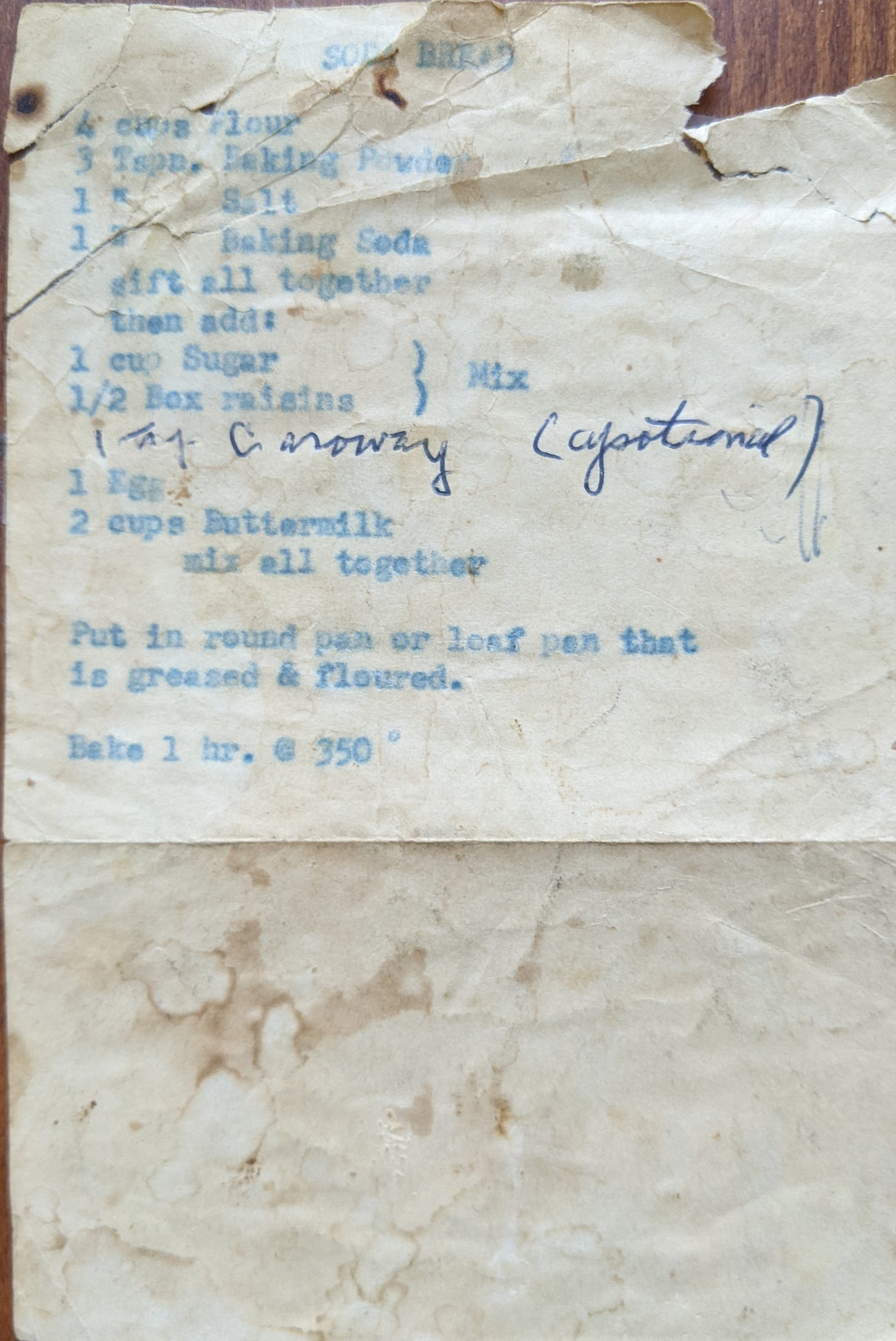

My grandmother’s recipe for soda bread is equally complicated. . . .

Mary Sheridan’s Soda Bread Recipe

My mom claimed her recipe was her mother’s, Mary Sheridan, who arrived at 18 from Glen, a minuscule village in Donegal. Every year I pulled out the tattered stained piece of paper she typed it on, and every year I baked it. The family cherished it. Friends said it was the best soda bread they ever ate. Well, of course. It was the real thing, straight from Glen in Donegal.

And then I lost the recipe. It was a year after my mom’s death, and my sister, Sue, was off somewhere in the world teaching. I was forced to search through books and, of course, the internet, where I found a bunch of recipes that weren’t anything near the bits of Mary Sheridan’s original that I remembered. The ingredients’ measurements, especially for the crucial buttermilk, were usually off. All incorporated butter. Raisins were often missing. None listed caraway seeds.

Then I opened Mark Bittman’s How to Cook Everything and discovered his recipe. Except for the sacrilegious use of a food processor, the recipe read exactly the same as Mary’s. Martha Stewart had one, too, although it called for brushing the dough with egg white to create a sheen. Neither stressed the importance of baking it in a cast iron skillet.

I called my sister immediately upon her return.

“Mom’s soda bread recipe was her mom’s, right?”

“Yeah.”

She sounded like she couldn’t believe I would even be questioning it. I then referred to Bittman and Stewart.

“Can’t be.”

“The only difference is Bittman uses a food processor. And Stewart does an egg wash.”

Sue dismissed the food processor because as we both know it’s important you feel the flour to see if its silky or, like mine has been, too dry and may need an extra splash more of buttermilk for everything to come together.

Instead, she went straight for the egg wash’s jugular. “That’s for the rich who can spare an extra egg or want to show off.”

And that, as far as my sister was concerned, was that.

But it’s not hyperbolic to say the world shifted a little in having to contemplate the possibility that a recipe core to my identity, that was passed from one woman’s hands to another and then two others, could not be a tangible link to our ancestors.

I finally found the slip of paper with my mom’s recipe stuck in her old cookbook. Yesterday I tried to be professional and baked both Bittman’s and Stewart’s. As Sue predicted, the food processor refined the texture of the dough. And once more, my big sister was right—the egg wash elevated the look of the bread to a hoity-toity level.

In the long run, Mom’s mom’s soda bread might not be the unique recipe I always thought it to be. Instead, its originality is in the technique taught to Mary Sheridan by her mom in the cottage kitchen in Glen. She taught my mom and our mom taught Sue and me.

THE ORIGINAL SODA BREAD RECIPE, GOD DAMN IT! (with special technique notes in italics)

4 cups flour

3 teaspoons baking powder

1 teaspoon baking soda

1 teaspoon salt

1 cup sugar

About 2 cups raisins

1 teaspoon caraway seeds My mom said caraway seeds were optional, but she always used them.

1 egg

2 cups buttermilk

Preheat oven to 350 degrees.

Grease and flour a cast iron skillet. Put to the side.

In a large bowl, mix together with your hands the flour, baking powder, salt, baking soda, and sugar.

Mix in the raisins and caraway seeds. It’s important to make sure the raisins are well coated with flour or they’ll end up at the bottom of the bread.

Make a well in the middle of the dry mixture and add the egg and the buttermilk. Make sure your hands are dusted with flour and begin mixing everything together until the egg and milk are fully incorporated. The dough will be sticky and some dry bits won’t mix in, but that’s ok. Extremely important point: DO NOT HANDLE THE DOUGH ANY MORE THAN YOU HAVE TO. A GOOD TURN OR FOUR SHOULD BE ENOUGH!!!

Turn the dough out directly into the skillet and shape it until it’s perfectly round. Take a sharp knife and make a cross on top.

Bake for 1 hour.

I hated St. Patrick's day as a kid because I didn't like the color green in my clothes so I never had anything green to wear. I spent the day avoiding other kids that were trying to pinch me because I didn't have any green on. I still don't like green nor do I have clothes with green on them, but at least I don't have to avoid others trying to pinch me.

Up Donegal! ☘️