The owner of our small market was on the phone. I was next in the checkout line. He hung up, descended from a high platform where his desk overlooked the store, then stopped between the two young women absentmindedly sliding groceries across scanners.

“The governor is shutting down the state tomorrow,” he said to no one in particular but loud enough for all of us to hear.

This is what I did next: Paid for the last pile of groceries I would buy from the market for several months, then crossed the street to Rite Aid, where I scooped up armfuls of decongestants, cough syrup, Tylenol, and two brand-new thermometers to replace an ancient one. Back home, my fairly pessimistic little heart noted that this stash wouldn’t last two days because it was certain someone I loved or knew or even I was going to come down with COVID. That’s why I retrieved Florence Nightingale’s Notes on Nursing (still required reading in nursing schools), Fannie Farmer’s Food and Cookery for the Sick and Convalescent, and a file full of pamphlets, photocopies of 18th-century family papers, and several thumb drives to reacquainted myself with invalid cooking and the art of caring for the sick.

Up until the early 20th century, nearly every cookbook contained a section devoted to dishes specifically for the sick room. In general, they were made by women who were expected to be skilled in relieving fevers, intestinal complaints, headaches, gout, toothaches, snake bites, sword wounds, and every other human infection. Their experience and knowledge could rival doctors’ and, until there was a general acceptance that doctors knew what they were doing and not all hospitals were death traps, people were treated at home.

Invalid cooking addressed the central quandary of caring for the sick—they must be fed even in their most queasy state. Nightingale instructed that dishes should entice the appetite and, if not thoroughly relieve symptoms, not hinder recovery. The ingredients should be the best and the freshest available, the dishes prepared with utmost skill. “Remember that sick cookery should do half the work of your poor patient’s weak digestion,” she said.

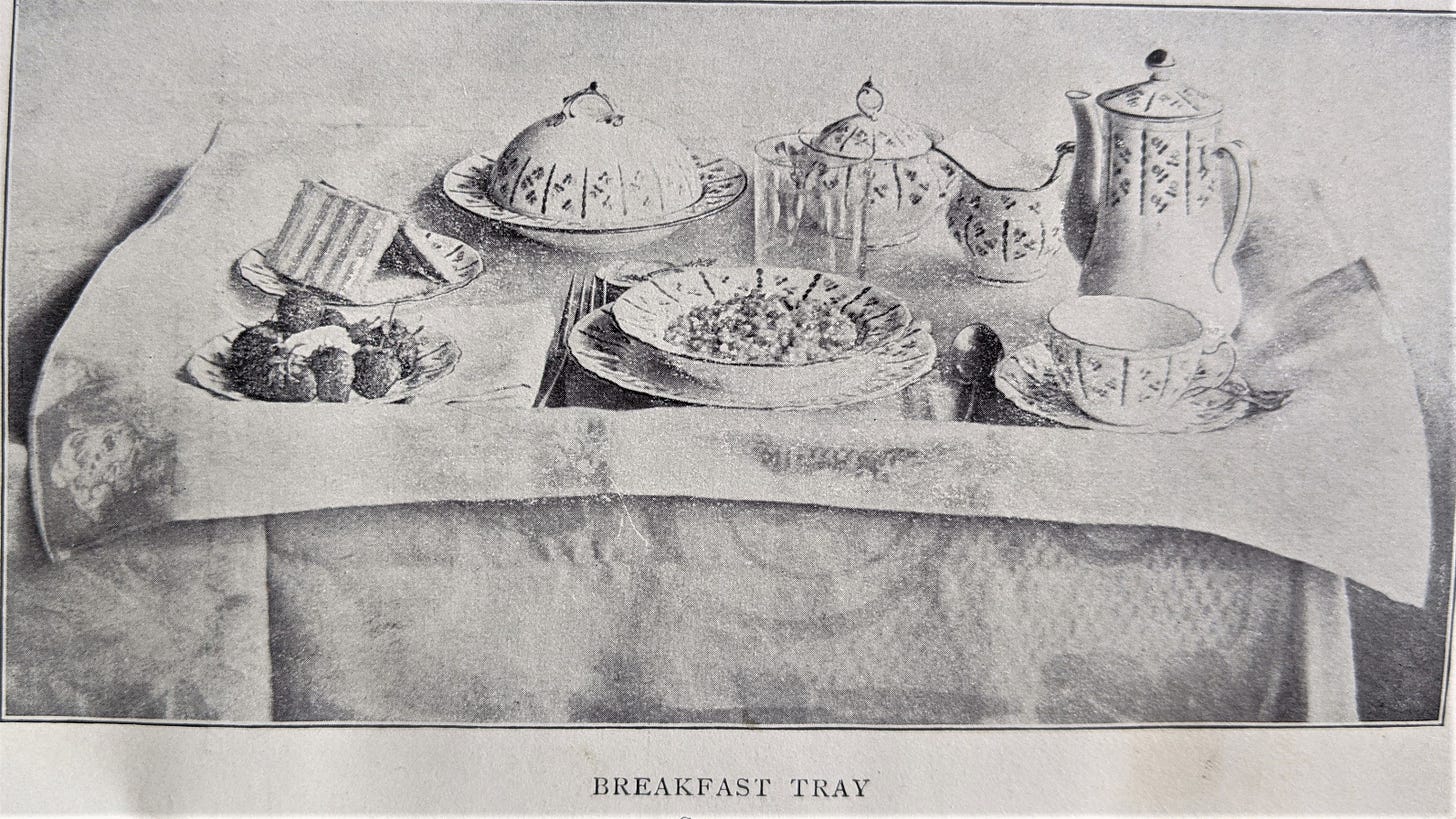

Beyond the actual flavor of the food, equal thought was given to how it appeared and was to be served. Feeding the sick, Nightingale claimed, was about seduction. Meals should be presented on a pretty tray, set with the best china, served punctually at regular intervals and in small quantities. When the patient was through eating, the tray was to be removed from the room quickly to prevent the lingering scent of food from upsetting the patient’s stomach. If little or nothing on the tray was touched, another attempt should be made in an hour with another dish, perhaps something as flagrantly flirtatious as a sweet custard or flavored crushed ice.

Teas and clear broths or consommé were advised for the early stages of illness. Teas may vary—a weak black with milk and lots of sugar, which will help revive flagging spirits; chamomile to reduce stress; or sassafras to settle upset stomachs. Carefully degreased broths, beef teas (essentially a weak bouillon made from good-quality flank steak), or a robust consommé are helpful in maintaining nutritional needs and replenishing lost fluids.

Fresh lemon, grapefruit, and orange juices diluted with water and served in a tall glass over plenty of cracked ice are most welcome in the afternoon. For dinner, depending on the state of the stomach, start with toast, dry for the most nauseous part of the illness or maybe dusted with cinnamon sugar or lightly glazed with honey to make it more palatable. As the illness subsides, and fever or congestion lessens, the menu should concentrate on strengtheners: oatmeal gruels; shirred eggs; pasta with finely chopped vegetables; delicately poached chicken or white fish, dampened with a little wine sauce. Before the patient goes off to sleep, a toddy of hot liquid is often beneficial—anything from fortified herbal teas to warm milk flavored with a teaspoon of wine or brandy.

If our experience over the last year and a half has taught us anything, it is the necessity to once again learn how to tend to each other’s needs. With hospitals, doctors, and nurses overwhelmed, a great many of us voiced fears of being left alone to cope with COVID’s effects. Something very valuable has been forgotten along with the recipes and teachings of invalid cooking. Certainly, none of these dishes should supplant prescribed medicine, yet prepared carefully and used judiciously, most of invalid cooking proves to be an invaluable healing ally, particularly beneficial in the management of symptoms.

With summer arriving in two weeks and restrictions lifting, if not disappearing altogether, the following recipes are formulated to perk us up. Two are from the 18th century and require gathering fresh herbs. (The Chestnut School of Herbal Medicine is a good source for safely identifying and gathering herbs.) Two require a good measure of vinegar, a safe ingredient that has been valued for centuries for medicinal use. I have made and tasted all the recipes.

A Spring Tonic

(From the Van Rensselaer family’s cookbook)

15 meadow plants, leaves, and roots, gathered while they’re still young*

1 bottle good white wine

1/4 cup honey

1 1/4 cups good fruit brandy (homemade is best)

Clean the meadow plants under a strong stream of water. Shred the leaves and dice the roots. Place the leaves and roots in an earthenware or glass jug or bowl and pour the wine over the plants. Cover with a cloth and let steep for at least three days, stirring occasionally.

Remove cover and pour the wine and plants into a stainless steel saucepan. Bring to a boil over a medium flame. Remove from heat and strain the liquid through a fine-meshed sieve into a bowl. Press the leaves and roots with the back of a spoon to extract any remaining juices. Discard the leaves and roots.

While the liquid is still hot, add the honey, stirring until the honey dissolves. Let cool completely. Add the fruit brandy and stir.

Pour the liquid into a container (a wine bottle is preferred, but you can also use a plastic milk carton) and let sit in a dark cool place until the following spring. It can be bottled or used directly from the container.

Take two tablespoons in the morning and at night.

*Suggested plants: licorice, milk thistle, yellow dock, wild thyme, burdock root, dandelion, beets, parsnip, carrots, lovage, chicory root, wild yam root, nettle leaves, violets (leaves and flowers), mint, mustard greens, chickweed, watercress, wild arugula.

A Tonic Soup

(Recommended by Dr. John Fothergill, 1712–1780)

6 cups water

2 sweet onions, sliced

2 fresh burdock roots

1/4 cup yellow dock root

½ cup dandelion roots

1 fresh young beet

1 young parsnip

1 new potato, medium diced

2 young carrots

2 ounces kelp

1 lovage stalk, chopped

1 cup chopped dandelion leaves

1 cup chopped yellow dock greens

1 large garlic clove, diced

Fill a large soup pot with the water and add the onion, roots, beet, parsnip, potato, carrots, kelp, and lovage. Bring to a simmer over a low flame and cook for about 30 minutes, or until roots and vegetables are tender.

Add dandelion leaves, greens, and garlic, and simmer only a few minutes more, just until the greens are wilted.

Makes 4 to 6 servings.

Dandelion Salad to Cleanse Winter Blood

(As told to me by Miss Glover, Atlanta, circa 1979)

1 bunch fresh young dandelion leaves, coarsely shredded

4 strips bacon

1 firm sweet onion, cut into thin slices

salt and pepper to taste

3 to 4 tablespoons good cider or herb-flavored vinegar

Sort through the dandelion leaves and discard stems and any leaves that seem tough. Place in a large salad bowl.

In a skillet, sauté the bacon until crisp. Add the onions and briefly cook, turning once or twice just to wilt. Remove bacon and onions with a slotted spoon and mix in with the dandelion leaves, tossing briefly. (You don’t want to drain the bacon and onions, but let the grease gently coat—not drown—the leaves.)

Sprinkle the salad with salt, pepper, and the vinegar. Adjust seasonings to taste.

Makes 2 servings.

An Oxycrate

(Recommended by Dr. Robert Wallace Johnson, Nurse’s Guide, and Family Assistant 1719/1720)

4 tablespoons white wine vinegar

1 ½ ounces honey

1 quart water

Mix all together in a bottle and cork. Lay down for a week or more. Take 1 tablespoon in the morning.

Thanks Kate! I think of it as one of cooking's lost souls! Put aside the strange/dangerous ones (cocaine does not cure nymphomaniacs!), there's so much wisdom in them

I love this post, Pat. It brings back memories of some of my mom and grandma's cookbooks and seeing that section in the back about cooking for those who are ill. Thanks!