Great cookbooks are smudged. Stained, dogeared, spine cracked. One of mine is Soul Food, Classic Cuisine From the Deep South by Sheila Ferguson. I bought it when it was published in 1989 and, by now, have cooked most of the dishes in it, including pig’s feet which were always on prominent display in the meat store when I lived in a mostly Hispanic Brooklyn neighborhood. I made them for my dad who had come up to inspect the seriously dilapidated house the husband and I bought and somehow missed the ceiling holes and former chicken pen in the dirt basement (with a sick chicken left behind by the previous owners). He walked around the neighborhood, saw the feet in the window and, with his urging, we took a bunch home. None of my books except Ferguson’s helped me figure out what to do with them. Four hours later, my parents, three-year-old son and unsuspecting husband sat down in the yard under the dead apple tree and feasted. My dad loved that house.

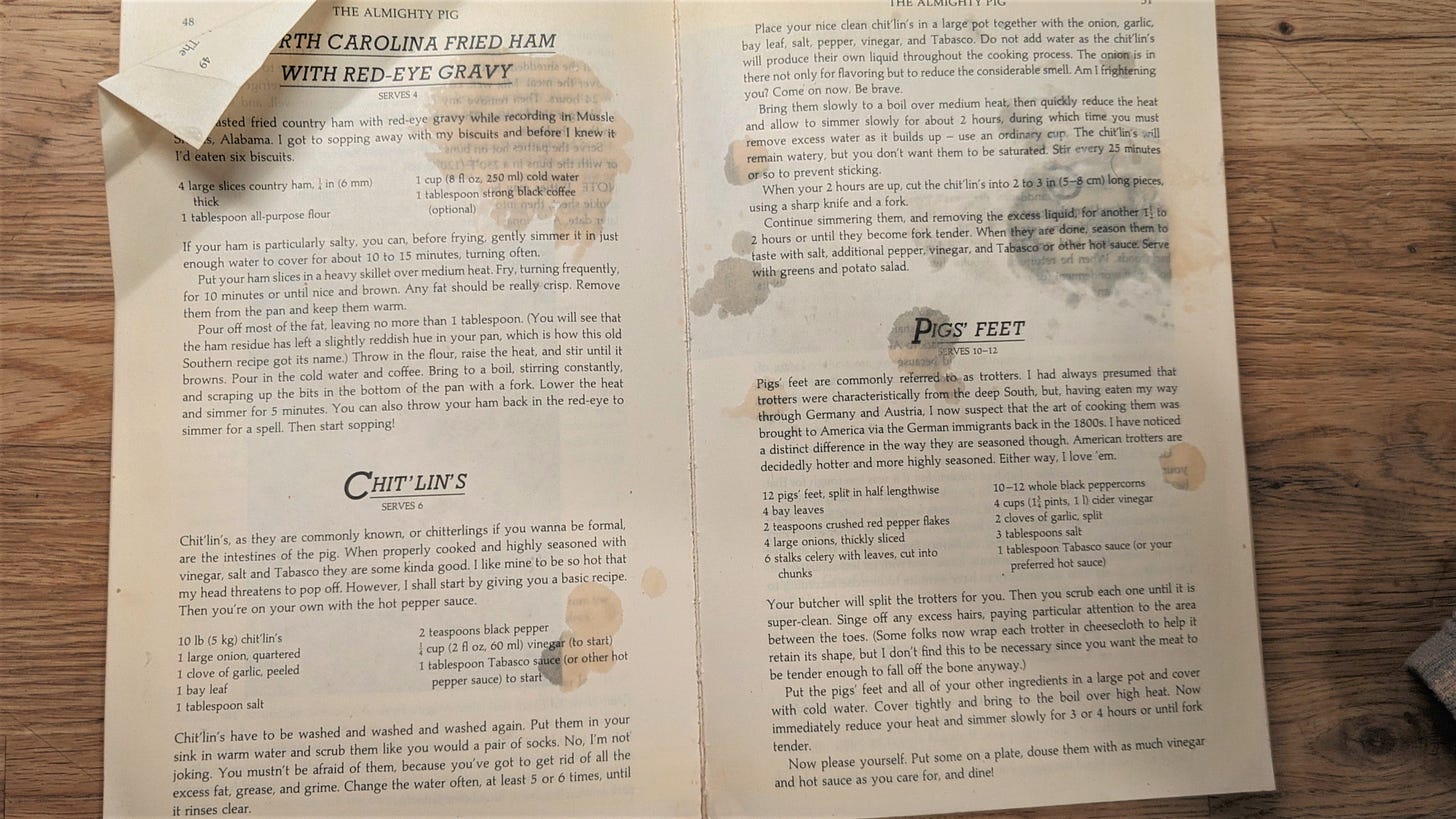

Southern food was something of a rage in New York City restaurants then and, because I was working as a restaurant reviewer at the time, I ate in a lot of them. The famous one in Harlem, a short lived new one in midtown and a rather fancy one in the theater district. Red-eye gravy, chit’lin’s, macaroni casserole, fried fish, ham hocks and collard greens, most of it so wonderful I still retain flavor memories of them. Just like I did with every assignment given for other cuisines, I researched and cooked to understand what I was eating. In the end, I thought I did a pretty good job. The editor did, too. A few months later I found Ferguson’s book and realized what a close-to-hatchet job I had done.

Ferguson was the lead singer for The Three Degrees and her book is in great part a memoir to impart to her daughters the vastness of their cultural and culinary heritage. Her advice about what it takes to understand a recipe should be etched into every bone that stands at a stove.

To cook soul food you must use all your senses. You cook by instinct but you also use smell, taste, touch, sight, and, particularly, sound. You learn to hear by the crackling sound when it’s time to turn over the fried chicken, to smell when a pan of biscuits is just about to finish baking, and to feel when a pastry’s just right to the touch. You taste rather than measure, the seasonings you treasure; and you use your eyes, not a clock, to judge when the cherry pie has bubbled sweet and nice. These skills are hard to teach quickly. They must be felt, loving, and come straight from the heart and soul.

One family, rooted in the history of America, generations braided together in surviving horrible pain and adversity, all the while playing a part in one of the world’s great cuisines. Food is not often given its indispensable due in forming the character and history of a people. Ferguson’s book is the one I find myself sifting through to try to comprehend this moment in our country. Her unsparing story–pointed, funny, warm, erudite–gives me hope we will find our way to a common table.

For the basic framework of this style of cooking [soul food] was carved out in the deep South by the black slaves, in part for their white masters and in part for their own survival in the slaves quarters. As such, it is, like the blues or jazz, an inextricable part of the African-Americans’ struggle to survive and express themselves. In this sense it is a true American cuisine, because it wasn’t imported into America by immigrants like so many other ethnic offerings. It is the cuisine of the American dream, if you like. Because what can’t be cured must be endured.