I hope you enjoy this serving of America Eats! We only grow by word of mouth, so please share this newsletter with someone you think might enjoy discovering bits and pieces of our country’s food culture and history!

Food has always been among a church’s most potent tools for creating and maintaining a fold, and at times for supporting the surrounding community. In a strictly culinary sense, the great thing about church picnics and suppers is that they display and uphold local dishes—and, of course, show off their congregation’s cooks.

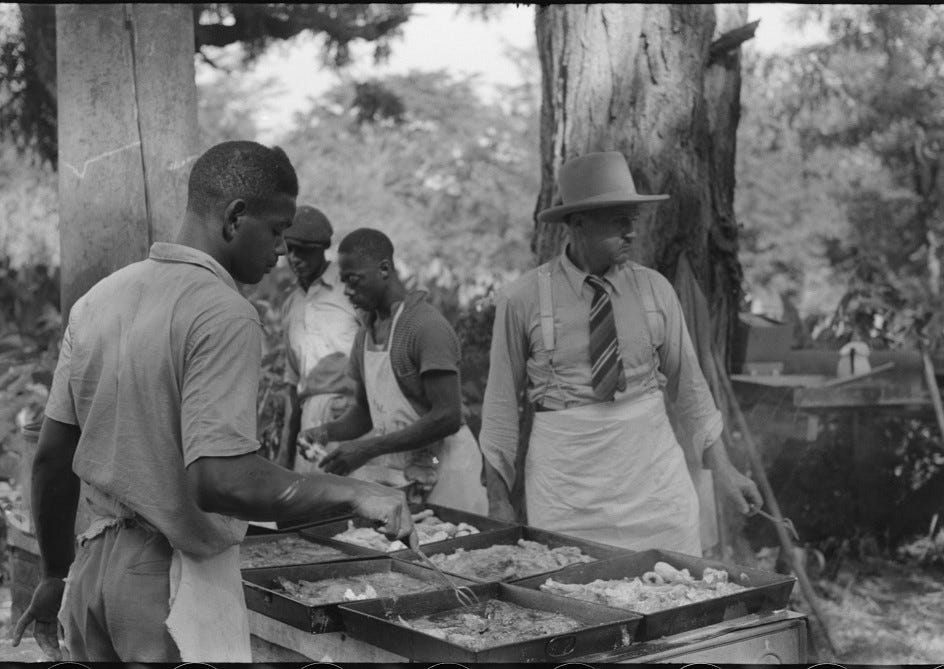

The photographs below offer glimpses of church gatherings from the later years of the Depression. The first group is of an annual parish event where the whole town was invited; the second is of a revival gathering; and the third is an example of desperately needed charity that crossed—somewhat uneasily—between two dominations. They represent their era and yet it wouldn’t be hard to discover their counterparts in the ways churches helped many of us through these dispirited times.

Summer church picnic on the grounds of St. Thomas Parish, a Catholic church in Bardstown, Kentucky. St. Thomas, founded in 1808, has a deep history in Kentucky, not a particularly Catholic state. It was not unusual in the south for Black men to be hired as cooks—not servers—for church and social barbecues and fish fries. Their recipes and techniques became something of a part of a town’s bragging rights, but they held their recipes close no matter how many times, or by whom, they were asked to share.

Both photographs are entitled “outdoor picnic at an all-day ministers and deacon meeting near Yanceyville, Caswell County, North Carolina.” The woman at top appears to be forming biscuits.

The mines at Jere, West Virginia, were shut down in 1935, three years before these photographs were taken. The caption reads as written “Much of the food brought into abandoned mining town of Jere, West Virginia from other parishes. There is a great deal of “hard feelings” and many fights between Catholics and Protestants. Miners as a whole are not very religious, many not having any connections with church, though they may have religious backgrounds. Hard times has caused this to a certain extent. As one said, “The Catholic church expected us to give when we just didn’t have it.”

The building in the first of this grouping had been used as Jere’s central church and community meeting place. The men are unloading provisions. Below, people say grace around a meager table.

All of the photographs were taken for the WPA’s Farm Security Administration and happen to represent the work of Marion Post Wolcott from 1938 to 1941. But many of the 20th century’s great photographers got their start in the administration by traveling the country recording the ways Americans lived through the Depression. They included Russell Lee, Arthur Rothstein, Dorothea Lange, Marjory Collins, and Ben Shahn. The photographs were often used to illustrate many of the publications written by writers for the Federal Writers’ Projects.

Being a strident broken record about this, I’m once again screaming that, because these programs have proven to be an invaluable depository of American history, they must be resurrected now. Affected by the social and political upheavals of this time, we are going to emerge from this period a different country just as we did after the Depression. It needs to be recorded for the future in all its disparateness. And, of course, artists and writers desperately need work.

Do you have a family photo of a gathering you’d like to share with us? Post it in the comment section!