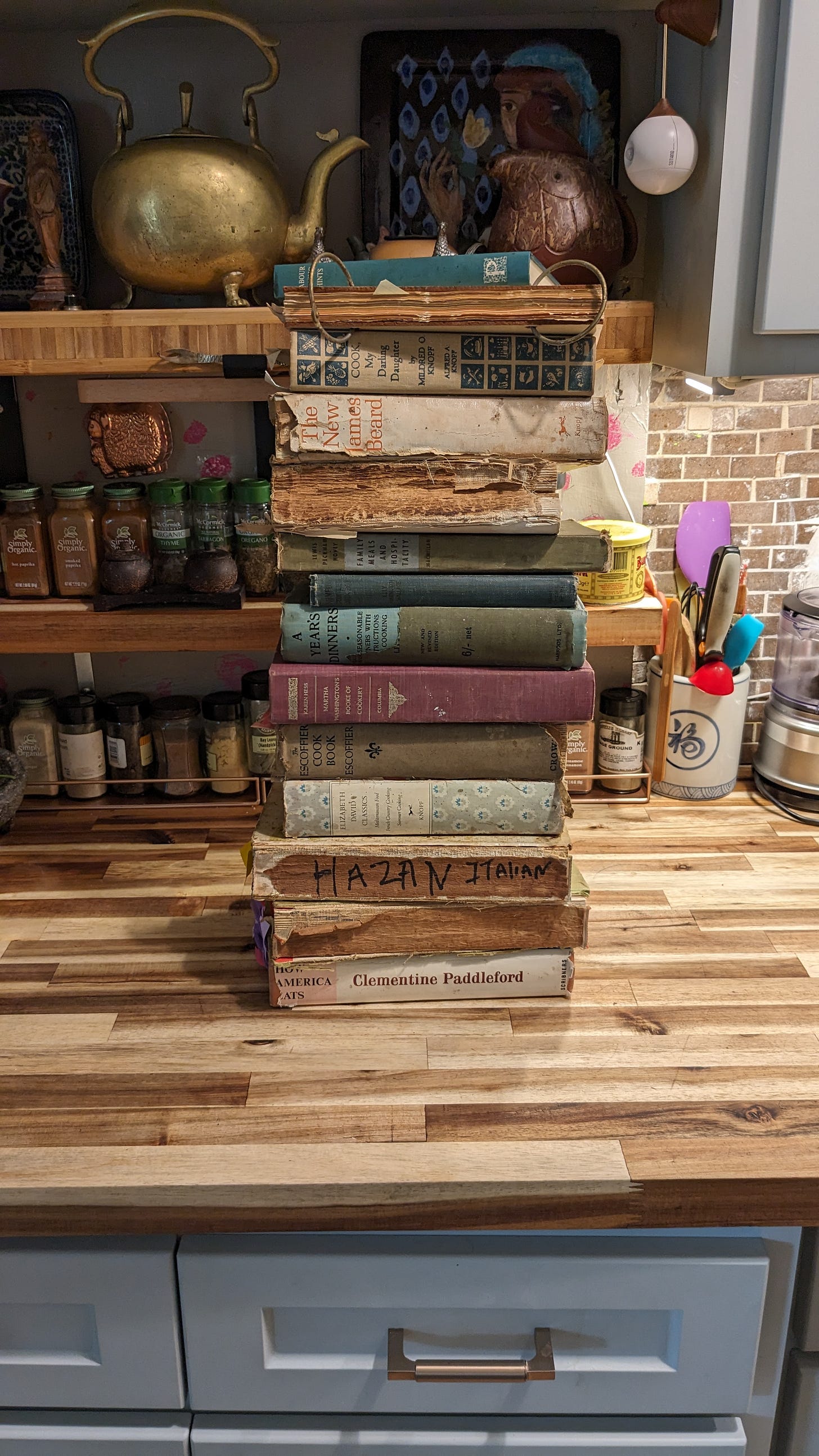

I have more cookbooks from the late 1890s to the 1960s than from the decades afterward. The new cookbooks represent my usual feeble attempt to keep up with current food writers and trends. The old cookbooks could be passed off as historical sources. The truth is very little in the new books hold my attention while everything in the old books fascinate me.

Old cookbooks are like messages in a bottle, carrying back to us the ways of another kitchen era. Households were content with one or two and treated them in many ways like the family bible, to consult for daily instructions and be paged through for inspirating, comforting pathways. Kept in kitchen drawers or a nearby shelf, they often served as a depository for everyday events.

The oldest recipes rarely give exact measurements or clear directions because there was the assumption that the reader had already been schooled at an elder’s side. Ingredients have different names than their modern counterparts, or have become rare, or no longer used. The twentieth-century showed an increasing reliance on mass-produced canned and frozen products and the dawning influence of foreign cuisines. Food memoirs gained in popularity. World events encroached in the cookbook aisle with subjects ranging from how to manage World War II food rations, learning the art of vegetarian cooking, and time management tricks for women who no longer wished to be tied up in the kitchen. Modern inventions received their due in publishing with the widening availability of food processors and microwaves, and the development of home versions of professional equipment.

More valuable, though, is the way these eras’ cookbooks stored bits and pieces of their owner’s private life. Torn scraps or neatly cut-out recipes from local or defunct newspapers and magazines are common; surrounded by the record of local happenings make them even more interesting. It is not unusual to find slips of paper on which was written the previous owner’s family dishes—for instance Aunt Dottie’s famous lemon pound cake or Sister Protase’s crab cakes, the most popular dish at her church’s 1968 carnival. Lucille May’s 1954 report card, forgotten in the Family Meals and Hospitality (The Macmillan Company, 1951) considered her average grade of 75 enough to be promoted to the fourth grade. An advertisement for Humphrey’s Marvel Witch Hazel—sure to cure neuralgia, infant excoriations, and dull hair— slipped out of Martha Schwenzfeir’s copy of The Rumford Complete Cooking Book (University Press, 1908). Lena Dent’s obituary (passed on December 10, 1949 at 38) was cut from the Newcastle-Upon-Tyne’s Evening Chronicle Newspaper and preserved in the beef section of A Year’s Dinner (Northumberland Press, Limited, 1930). A letter from Botswana on blue Aerogramme paper fell out of the 1965 edition of Michael Field’s All Manner of Food. A small envelope containing two pressed and faded flowers—a rose and maybe an iris—nestled in the potato section of The Settlement Cook Book (Simon and Schuster, 1924).

I looked through my collection and found that the many purchased beginning in the 1990s contained nothing of my cooking and professional life. The four bought before these years, and were for a long time the only ones I owned, represent the early years of marriage and motherhood. Their covers are battered, pages liberally splashed, spines split by being pressed opened, all of them stuffed with clippings and cooking demonstrations handouts. Among the unearthed gems were my mom’s recipe for escarole soup; a postcard from China sent to us in 1987; a Valentine my son made in preschool—crookedly cut out red construction paper heart and crushed paper doily; a 2008 bill for $83.10 for blood work; a friend’s poem typed on lined paper; a Christmas card from someone I no longer know.

It could be that I stopped using my cookbooks this way in the late ‘90s because I began to have so many that none were special. Another reason surely was the general havoc of a household erupting with teenagers. But I also think it was because there started to be an increasing reliance on the internet and social media instead of print publications; email and texts in place of personal communications.

Whatever I have since deemed to be worthy of keeping if only for a moment may be buried within drawers and boxes scattered around the house and basement. No longer centralized within my cookbooks they won’t be found without commencing a very concentrated search. They will never again be puzzled over as curious reminders of a past serendipity stumbled upon in the course of cooking an ordinary dish.

Sister Protase’s Popular Church Carnival Crab Cakes

(As found)1 medium sized finely chopped onion 4 tbsps. butter and 4 tbsps. shortening 3/4 cup flour and 1 cup milk 2 tsps. Worcestershire Sauce 1/2 tsp. dry mustard and 1 tsp. salt 1 pinch mace and 1 lb. crab meat Melt the butter and shortening in top of double boiler. Add onion and simmer over direct heat, slowly (don't burn), until onion is tender. Take pan from heat and let cool a moment. Stir in the flour. Be careful the butter mixture isn't too hot or the mixture will be lumpy. Stir in the milk GRADUALLY, then the seasonings. Set over the boiling water and stir constantly until sauce is blended. Pour this thick sauce over the picked-over crab meat. Mix well, and then refrigerate it overnight. Shape this into patties approximately 1" thick. Roll them in breadcrumbs to coat all over. Lower them into hot fat--deep enough to cover completely and fry to a golden brown. Lift out and let drain a moment on absorbent paper. Serve piping hot.

She's my favorite girl!

Love seeing Clementine Paddleford there :)