The Last Bar Stool

A considerable town's history through its corner bars.

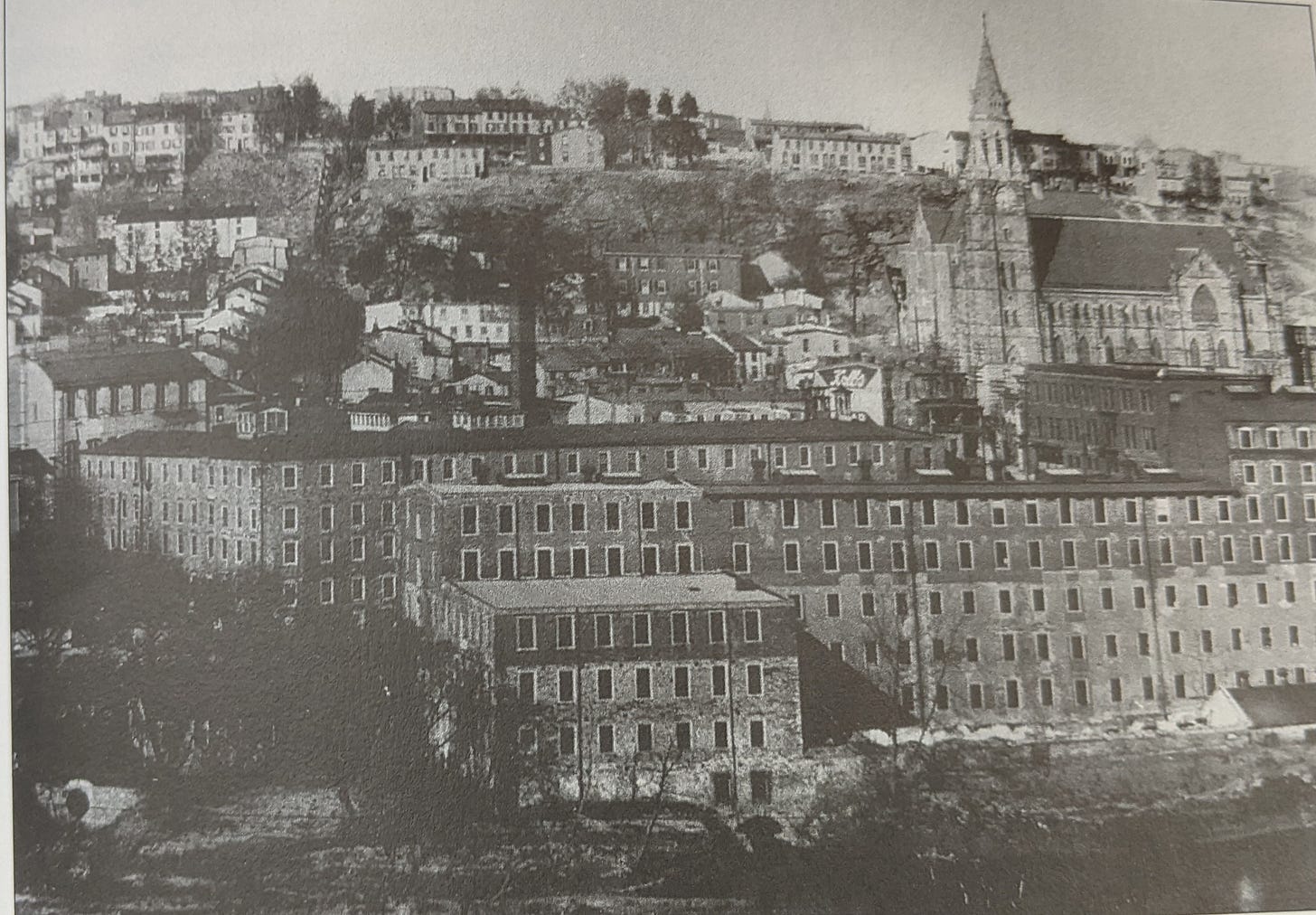

The yarn and wool mills that border Manayunk are separated from the Schuylkill River by a canal surveyed by George Washington and dug by Irish immigrants. The first mill was built in 1813. By the Civil War, there were an additional 15 spinning out textiles, wools, and paper. Each day, bales of finished merchandise were packed onto the canal’s barrages and floated through the locks on their way down to the Philadelphia wharves.

The town grew up steep hillsides, the mill workers’ small rowhouses built from the same gray mica-flecked stone they clung to. Tall Catholic church steeples soon appeared across the town as if to catch the houses from sliding down into the river. Each represented the nationalities that successively immigrated in the 19th century and who were drawn to Manayunk by the promise of the mills: Irish, Poles, Germans, and Italians. Two very old Episcopalian churches represented the English mill owners who had settled in the18th century. African-Americans freed since the Revolution carved a small wooden church in a grotto nestled precariously under a hillside ledge.

Manayunk burst with prosperity to become one of Philadelphia’s most consistently successful business districts. On one side of Main Street were the mills’ business offices, the newspaper office, and banks. On the opposite side there were haberdashers, grocers, jewelers, a hotel, barber shops, The Empress Theater, and Propper Brothers Department Store. Scattered between were several table-cloth restaurants, soda shops, and gentlemen saloons.

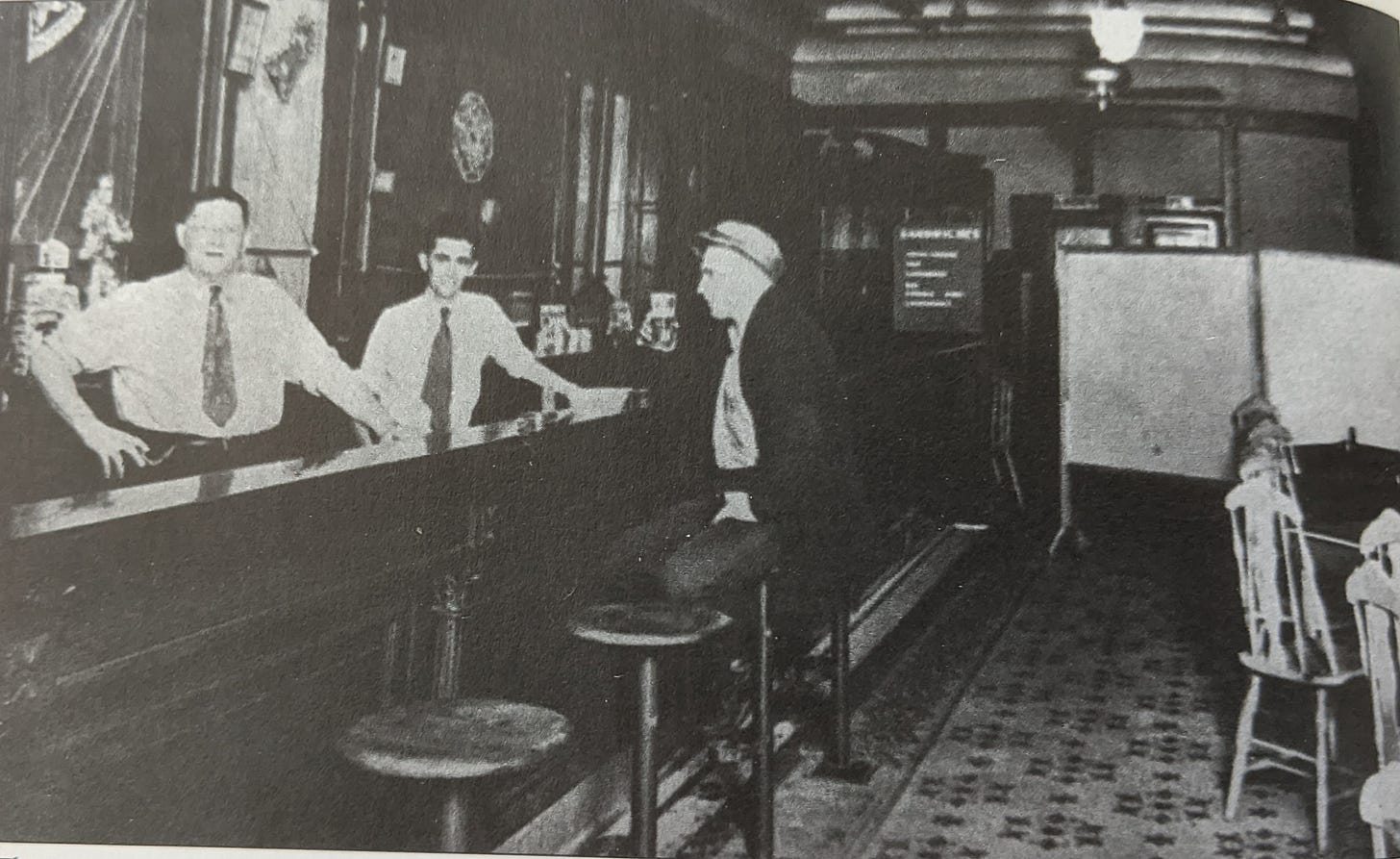

In the next street, the blocks of rowhouses sometimes ended in corner bars. They were a source of extra income for the families that often lived in the rooms above. If the family was ambitious, they offered another revenue in the form of cooked dishes for the patrons, mainly soups, stews, and sandwiches. German-style hot dogs were on several menus. The bars were emporiums where most could afford to gather, bring girlfriends and wives, host family events and holiday gatherings, celebrate momentous events, and honor the dead.

I know all this because I grew up in Manayunk. My dad thought nothing of taking his children with him if his duties as the head of the local settlement house required a visit to a bar. We would walk behind him up the worn marble step and through the tight doorway into a dark room smelling sharply of cigarettes and hard labor. The television droned, a juke box in the back skipped along from Elvis to Frank. Very rarely would there be women inside unless she was serving behind the bar. The men appeared mythical, big and solid in their stance, in a place that was theirs. They all knew my dad.

My mom characterized his position as akin to the village vicar. He was the person whose business was taking care of the neighborhood’s private distresses and concerns, empty kitchen cabinets, fraying marriages. He understood children who were becoming too familiar to school principals, recognized sons hanging in the streets, or daughters cavorting with the wrong people. He knew sympathetic judges and lawyers. His best friend, the local beer distributor, had people who knew people and personally opened deep pockets and a streetwise-kind heart. Before he settled down with the person he was after, my dad would guide us to a back table and bring over bottles of root beer and a bag of chips. If there was an unused shuffle board or pool table, he and the bartender didn’t mind us taking turns. Then he got down to his job of figuring answers and solutions to the troubles that had brought the men to one of the few places left where they felt they still had some purchase on their lives.

Later, in the car, my dad would dissect for us what business he had in the bar, never minding that others might consider the information inappropriate for a child to hear. We grew up in a fading Manayunk. The abandoned mills’ old walls were cracking, windows broken, the annual spring and fall floods eating at their foundations, and the canal dying through two hundred years of chemical runoff. He thought that the bars were a good way to educate his children in history, economics, and social welfare.

Bars are a community’s guidepost to the kind of stealthy changes that trail behind economic and society shifts. The corner bars lasted longer than the mills in Manayunk but they no longer bustled through the harmony of a work day. Then in the late 1970s and 80s drugs washed through the neighborhood. Main Street gradually became a collection of vacant buildings, with the only consistently thriving store a hoagie shop with pinball machines in the front and a lucrative fencing/gambling/drug stash business in the back. By then, the average household income hovered near or below the poverty line. All of this became visible in the corner bars. Some of them changed hands several times over, the original owners either retiring or no longer able to keep what was happening outside from crossing their doorstep. Their regulars gradually stopped coming or died and were increasingly replaced with what my dad referred to as creeps and punks. Many a time, a bar would lock its door at night and fail to open it the next morning.

Manayunk’s change of fortune turned again in the late 1980s. Like many places across the country with a handsome stock of industrial buildings, artists moved in. Main Street gradually transformed into a noted restaurant scene. Whole rows of homes were torn down and replaced by stridently modern houses and apartments constructed on sharp inclines of shifting soft rock or flood-prone spits of ground along the canal. By 2000 college students discovered this overload of rentals, affordable if stuffed with roommates. Come the weekends, the hillsides screamed with their carousing voices stumbling up from anonymous big clubs and bars along Main Street. The people of Manayunk could no longer afford their houses or the price of a fancy hamburger.

And the corner bars—the few that remained along the blocks behind Main Street or tucked up in the hills—began to be called dives by strangers which, for a time at least, kept well-heeled visitors out. But then dives became synonymous with authentic and authentic meant an invasion and invasions sometimes meant trouble when the invaders felt unwelcomed and the natives felt dissed. The owners who accepted the inevitable decided it was better to either sell or renovate. Whatever they did, the corner bars of Manayunk no longer felt like home to the mill workers’ descendants.

A few years ago, my high school best friend and I met on Main Street for Sunday brunch. But it was before ten and all the restaurants were closed. The Cresson Inn on the next street over was not. When we walked in, two men sitting right inside the door shot us unwelcoming looks then went back to their beers and shots and the sportscasters parsing the day’s games. The owner hunched over the Sunday newspaper spread across the beer chest and didn't turn around at all. We took stools in the middle and our Bloody Mary order cemented the perception we did not belong.

At one point I asked the the man reading the newspaper if the owner was around. He said yeah, and came over. I told him who I was. I don’t know why except maybe I was looking for validation, some way to tell him that my friend and I belonged, that we had gone to the parish school and married in the churches a block away.

“I knew your father,” he said and jut his chin out to the wall behind us covered with crooked frames of faded photographs. They were of men in rolled-up shirt sleeves, elbows on the bar, pitchers of beer before them; young men in soldier uniforms spanning the 20th century wars; couples kissing in the back room; a parade along Main Street; the bar strung with Christmas lights; graduating high school classes; teenagers outside crowding around a 1950s era convertible; the bar owners family with different patrons over the last 50 years; and many, many, sport teams.

And there was the one with my dad. He stood in a summer business shirt with a porkpie straw hat pushed back on his bald head, the last man in a row of other men, one in a business suit, two others—the coaches—in tee-shirts, their faces shadowed by baseball hats. Knelling before them was a team of little kids in dusty uniforms with a tall trophy centered in the middle. Someone had scrawled with a thick pen across the bottom: “1968 21st Ward Champions.”

“I’m on the right,” the man said. A raw-boned sandy hair boy with a pitcher’s mite balanced on one knee.

He wanted our Bloody Marys to be on the house but I said my dad would murder me if I didn’t pay. Then I kissed his cheek and my friend and I left.

Months later my friend told me The Cresson Inn closed. That was two years ago and recently she sent me a link to the news that the bar was reopening under the proprietorship of a neighborhood guy who owned a restaurant in another fashionable part of Philadelphia. The son of the man I kissed had joined him and, as the publicity said, the new Cresson Inn would capitalize on its past as “The Original Yunkers” bar.

Here are a few corner bars that haven’t changed at all.

Ahhhhhh, Manyunk!!

Great piece, P.

My memories are scattered, but Manyunk was always the place I would mention if anyone brought up Philly.

Love the snippet about your Dad....I have such a clear picture in my memory from a photo I have.

This is a beautiful piece that brings a tear to my eye. My hometown is nearly unrecognizable and the adopted hometown where I have settled feels to be on the edge of a major transformation as climate refugees move to the area.