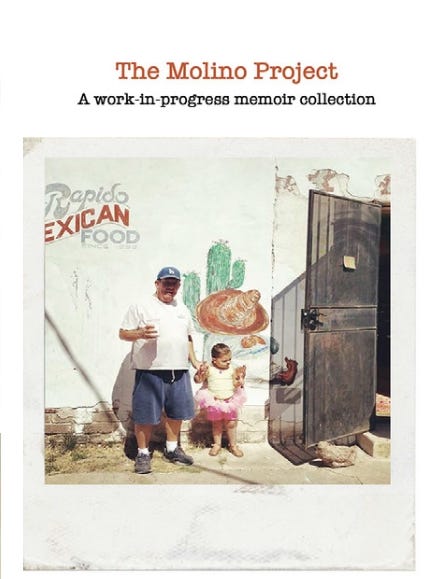

The Molino

An excerpt from a fine writer's memoir of growing up in the shadows of her family's Tucson tortilla factory.

Mele Martinez and I met at a dinner for new students in Goucher College’s M.F.A. program in Creative Non-Fiction. I unceremoniously glued myself to her because she seemed to be sharing my deep second thoughts about this endeavor. This was solely based on the observation that we were different than anyone else in the room: I was older with published books, she was an accomplished Mexican-American flamenco dancer from Tucson, Arizona. We eventually put our reservations to the side. What truly united us was writing, the ways we saw the world and the way we fit—and didn’t fit—into it, often through our relationships with food and cooking. Mele was the best writer in our class. That first week, she shared a knock-out draft of the story that would open her memoir, The Molino, about working as a child in the shadows of the monolithic molino in her family’s factory that each day ground the corn to make the family’s famous tamal and tortillas. The memoir, composed of interlocking short stories, continued to explore the history of her family and the broader Mexican-American community in Tucson through their food traditions and the effect of gentrification and poverty.

Mele has won a succession of awards and grants as she has worked on completing the book. It is more than time to share its beauty.

The following story tells of her father taking her and her brother, Ricky, to the San Xavier del Bac Mission on the Tohono O'odham reservation.

Popovers

by Mele Martinez

My father is like a priest in a pickup truck. He smells like corn and grease and Coors light. He pastors over us, teaching us his own way to know Tucson and missions and, like the wind, our almost invisible origin.

On Sunday mornings while my mother is at work or while she sleeps after a night shift at the phone operator’s switchboard, my father puts Ricky and me in his pick-up truck and drives us out to the reservation just a few miles south of our home. On the drive, we see the white plaster of San Xavier del Bac Mission punch through the woodland of mesquite trees and push against gray mountains and blue sky. We park in the dirt lot and drag our feet over gravel walkways up to the church founded by the Jesuit missionary, Padre Eusebio Kino. Made of piled stone and mud, the mission’s bell towers rise up like siblings, one done and one undone. The taller tower is domed and plastered white, marking its place in the desert like an inverted exclamation mark.

My father always points at the mission’s façade and retells the same ancient tale, but in his own tongue full of enigmatic doublespeak. “You see the cat and mouse?” he says, not really asking.

“I can’t see it,” I say.

“Where?” Ricky asks.

“Open your eyeballs,” my father badgers, pointing a crooked finger at the elaborate carved adobe and landing his heavy hand on the crown of our heads to force our gaze up higher. Eventually, we find the sculptural details: a skinny cat, an elusive mouse emerging from the baroque background.

“When the cat catches the mouse, the world will end,” he says, resigned like a prophet.

“How’s it gonna catch the mouse?” Ricky asks, loud and suspicious. There is never a clear answer. All that seems to matter to my father is the story, the words repeated like an incantation.

My head tilts back as we walk into the vestibule. I stumble on uneven floors, wondering how walls like these could ever crumble. In the mortuary chapel, Ricky and I kneel and repeat our memorized prayers. My father gives us coins to place in the collection box so that we can light a candle to add to the glow of the sanctuary. Only then we are cleansed from the sin of skipping Mass.

This is how my father teaches me to reconcile.

I light my candle, then I watch it glow among all the rest, making light in the darkness of the shrine. I look to the statue of the Virgen, her palms facing up into the blue hue of the nicho she stands in. I am not convinced she can hear my Hail Mary. I am not sure she can hear any of us at all. Maybe she is asleep with her eyes open, I think. Maybe she is too tired to listen to our repetitions. Or maybe she isn’t there just for us. Instead, she might be there just like us, waiting on God, like a hostess with a holy plate of food and napkin ready on the table, waiting to serve Him.

The mission is my favorite place to go to church because our repeated prayers, though clunky and absent-minded, are always sealed with a meal at the frybread stands.

My father calls them popovers. He is often demanding of servers in restaurants, but never with the Tohono O’odham ladies in front of the mission, the ones who stand all morning long wrapped in aprons, their hands waving over cauldrons of oil, their palms turning dough over and over. They say Padre Kino was the one to bring the wheat—both a blessing and a curse—to the Indians. Either way, my father couldn’t be happier. The expectation of frybread is one of the only things keeping him from chatting with everyone around him like he usually does in town. In line for popovers, he is more restrained, quieter. For him, this dough bubbling and glistening gold is sanctified. When we bite into the bread, we are baptized by the honey slithering down our fingers, down to our elbows.

This is how my father teaches me communion.

Popovers covered in powdered sugar or chile colorado, nesting in their paper plates in front of the mission--this is the kind of eating that helps me remember Jesus on the cross and Mary with her sorrows. My father makes sure that popovers will remind me of someone else’s sacrifice–of the blood, thorns, and tears painted on the walls and carved into rocks.

“The Indians,” my father said, “are smart putting this food right under our noses.” And I imagine it is more than being smart. It is more than survival. It is like making water into wine. And it happens every weekend.

When I am a teenager, my father will walk from Nogales to Magdalena, Mexico to make a manda. At the end of his pilgrimage, he will see where they keep Padre Kino’s bones after the priest succumbed to fever, was buried, or hidden, underneath the floor of the chapel at Magdalena. In the ruins of Kino’s frame and bronze image is a message of Christ and bread.

But Ricky and I never make a manda. We never see Kino's grave. We only see him on our drives back and forth in the desert, when my father points him out on the side of the road, a bronze statue of a man, robed and horse-bound with his hand on his heart. My father can’t cross the street without remarking on it, the same way he has to make the sign of the cross every time we pass a church.

I look at my father looking at Padre Kino who looks at the sky. And I wonder about how things will end. When we are gone, will there be little statues of us too? Or will we be buried and hidden like Kino’s remains?

Under the saguaro rib ramada at the mission, I imagine us all being pulled and cut, smashed and smoothed out in a Sonoran desert sculpture garden. First a belonging, then a missing part. I begin to feel uneasy on the gravel rocks. Just when I think I know where I come from, I am ground up again. Bucked off my bronze horse. Bones on display for all to see. I don’t feel like I’m from here, I tell myself. I stare at my half-eaten popover and squeeze it tight so that the wind doesn’t take it away.