I retrieved my Aunt Margie’s photo albums shorty after she died of COVID on December 22, 2020, at the age of 91. There were about 20 in all, starting in 1950, the year she turned 21 and was accepted into the Foreign Service. The albums begin with her first assignment in Frankfurt, Germany, where she worked as a secretary in a department charged with transcribing Nazi documents.

Margie grew up poor in a Catholic household of eight children, her grandfather, sometimes borders taken in to pay bills, and a mother and father who died before she was a teenager. She arrived in Europe about as unprepared and chaste as a young woman could be, still startled that she had even applied to the Foreign Service. After a month of training in Washington, D.C., she was booked on a boat that sailed to Amsterdam and then directed to a train that carried her to the bombed-out remains of Frankfurt. A bus picked her up at the train station and dropped her off at the State Department’s compound near the city’s center. For the first time in her life, Margie had her own bedroom in a large furnished apartment she shared with two other new Foreign Service women. Her work was difficult and enthralling, her social life invigorating, especially after she was shifted to Berlin. She picked up smoking and a taste for champagne. Gowns and high heels soon crowded the clothes she had brought from home. She fell in love with a married man. On weekends, she traveled to neighboring countries with friends where they were feted by State Department colleagues. She slept with her future husband, Frank Ward, the day after she met him. He was in the Service’s public affairs division, and for the next 24 years he and Margie worked and lived in Egypt, Cambodia, Indonesia, Australia, and back to Germany. In 1980, he reached the mandatory retirement age of 60 and they returned to the States, where they settled in a small town on the outskirts of San Francisco.

Each of her photo albums captures a different era in their lives. Hairstyles, fashion, and the landscape change. Frank stands with a revolving array of Far East generals and dignitaries. Margie entertains princesses, CIA agents, and consulate employees. Everywhere they go, they befriend local people. Once retired, their friends and relatives follow them from one house to another, one year to the next, for what looks to be lively get-togethers and celebrations. Margie and Frank grow old together.

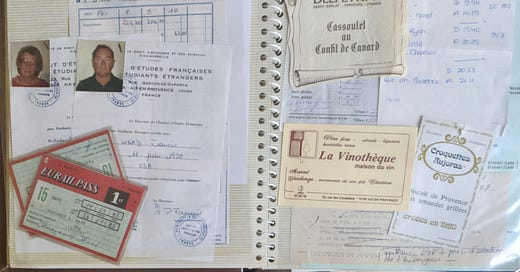

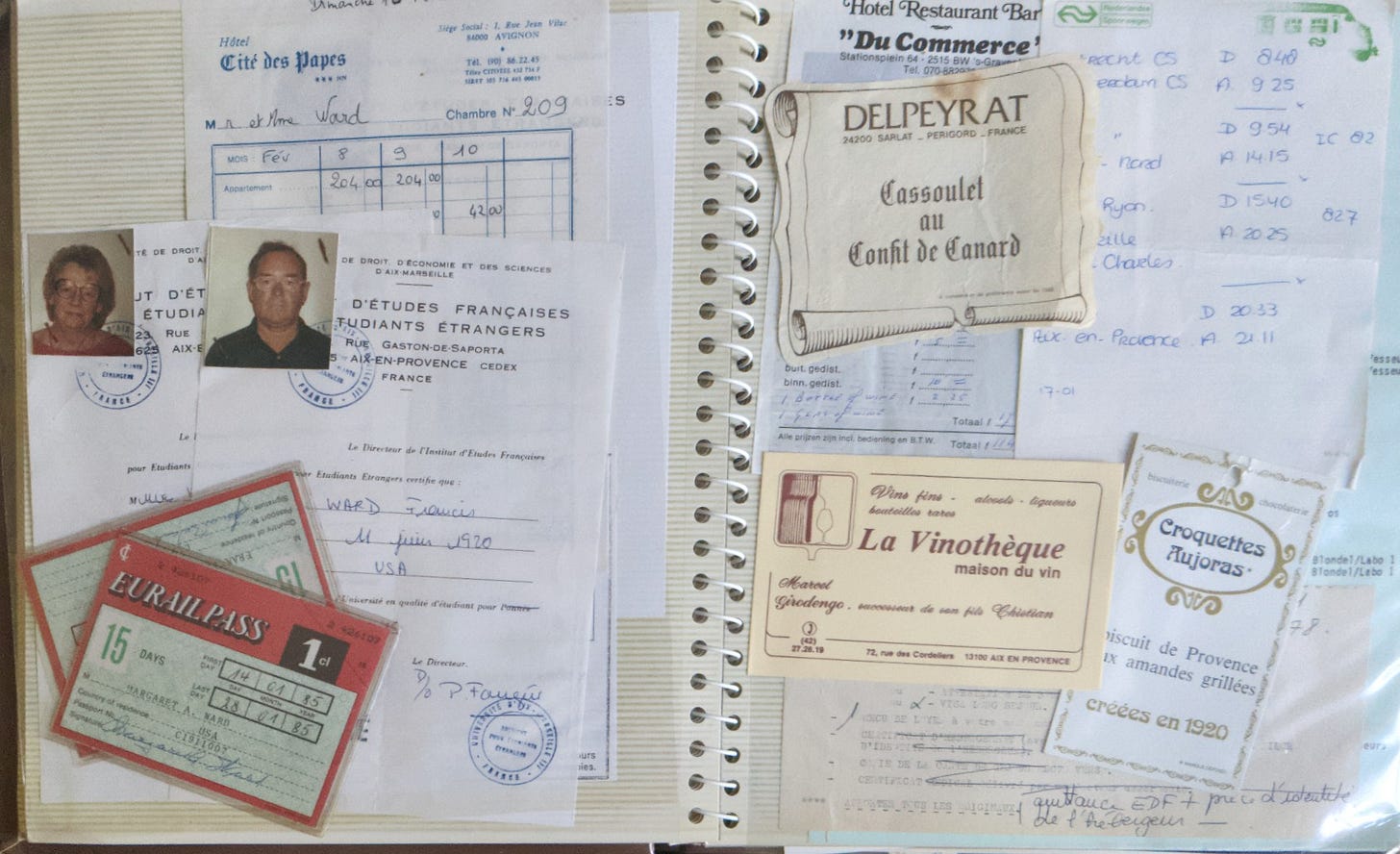

The album that has sat on the corner of my desk for the last year is different. It covers 1984-85, when Margie and Frank attended the Aix-Marseille University’s Institute for the Study of French. Their Aix-en-Provence was not the World War II tattered town that M.F.K. Fisher wrote about in her two books, Map of Another Town and A Considerable Town. The now restored town was one part touristy, one part unsullied charm. Unlike her other albums, there are no photographs to show what the town looked like. Instead, the contents record their year in lists and receipts. The protective vellum leaves preserve detailed itineraries of travel departures and arrival times; the university’s student information brochure; airplane and museum tickets; hotel bills; and shop labels. These artifacts seem much more intimate than photos could be, stimulating memories of common moments throughout the year.

What I adore the most about the album is the evidence of the food and wines Margie and Frank enjoyed in Aix-en-Provence. By this time, the poor young girl who had arrived in Frankfurt had long ago embraced adventurous unknowns. The South of France is, of course, legendary for its regional cuisine, and they probably had tasted it during previous European stays. But this time was different. They settled in and gave themself the leisure to take long country drives and slow trains to historical centers of French cooking, to Avignon, Toulouse, Marseille, and Bordeaux. Frank had a nose for back alleyways to discover neighborhood bars and tiny cafés. Margie easily made friends with nearly everyone she met, especially shopkeepers. They dined on freshly caught sardines and oysters on the Marseille quays and then came back a couple of months later for an extravagance of lobsters on the Quai des Belges. A weekly grocery list consisted of biscuits from Sarl des Croquettes Aujoras, confit de canard from Delpeyrat, and wine from La Vinotheque masion du vin. It doesn’t seem unusual today to do these things but almost four decades ago Frank and Margie were rare birds settled in not as tourists but as residents of the town.

Before my aunt and uncle left for their year in Aix-en-Provence, the family gathered at my parents’ house. Margie’s seven brothers and sisters and their spouses crowded about the kitchen, with nephews and nieces wandering in and out. My sister and I were put in charge of replenishing the platters of cheese and crackers, sliced meat and potatoes, with the famous string bean casserole on the side. An important chore was refreshing the men’s beers, the women’s cocktails, and Margie’s and Frank’s white wine. Most of the relatives could be said to hold the opinion that the trip was a little unseemly and extravagant, yet another example of how Margie had grown different from the rest of them. They had all ascended from their impoverished upbringing, but they had adhered to an all-important aspect of how they were raised, where the siblings stayed close by and where a year in France learning the language and eating French food was putting on airs.

When the year in Provence was up, there was another party at my parents’ house to welcome Margie and Frank home. Primal prejudices melted away with the stories Margie and Frank brought back, several of them resulted in a few of the uncles, my dad, and Frank recalling in detail their march through the same territory during World War II. The women enjoyed Margie’s intimate encounters with people and how the only French she became fluent in were curses. They brought presents of herbs and lavender, fine scarves, and intricately patterned Provencal tablecloths. On a plate beside the cheese and crackers was a tiny brick of pâté they smuggled through customs because their passports still showed the State Department’s stamp and their luggage wasn’t searched. A tin of orange-perfumed cookies joined the pies and cakes.

My aunt’s birthday is this Saturday. She would have turned 94, and we would have taken her to the same restaurant where we had celebrated her 90th birthday. My husband and I would have driven down from Brooklyn. The menu listed many Provencal dishes, and our long table would soon hold a plate of confit de canard and a selection of cheeses. Someone would order fish or lamb or rabbit, and for dessert there would be slices of orange cake, sorbets, and cookies.

At the time of her 90th birthday, Margie’s Aix-en-Provence photo album was still in her bedroom bookcase. But, as we did many times, we prodded her to tell us stories. Under the spell of our good meal, the two bottles of wine, and the celebratory glass of champagne, my aunt was delighted to go back to the year when she and Frank lived in the South of France.

Oh good lord, yes! and thank god some of them scandalized the family.

I bet she had so many great stories.