Tobacco Into Wine

A word about a changing agricultural landscape.

The ruins of century-old tobacco farms border Route 67. The ragged peak of a barn’s roof, a shredded curtain caught on shattered windows, the rusted hull of a tracker all taken over by mounds of kudzu vines and time. Along the sparsely populated backroad of Yadkin County, North Carolina, it can sometime feel like there’s only you and the ghosts of the past.

The decline of tobacco farming followed the rise of overseas competition in the 1990s and the collision with the government’s lawsuit against the major tobacco companies. Crop prices plummeted in just a handful of years. By 1997, people across the tobacco belt began to own up to the prospect that they were losing the fields their families had tended for generations.

Then the government stepped in. Money received from the tobacco companies in the court settlement was offered to any farmer who would churn over tobacco for a healthier crop. Soybeans and wheat fields spread across the valley.

A few years later, the state’s tourism bureau saw an opportunity and began promoting the idea of creating vineyards. They pointed out that it wasn’t just the yearly grape yield that would bring in money but the distinct, very profitable, possibility of visitors from all over eager to pay handsomely for a drive down country roads for an afternoon of wine tasting. It was not such a far-fetched scheme. Many farmers could recall relatives picking native scuppernong grapes or growing Concord grapes in backyards, not all of which went into pies and jams but were bottled for the family’s private wine cellar.

That was before Prohibition shut down all alcohol brewing. The region’s deeply conservative religious leanings pitched in, too. Dry laws, including in much of Yadkin County, were still being enforced in 2000.

Frank Hobson Jr. had to consider what was at stake. He was barely holding on to the land his father and grandfather steered through the Depression. Tobacco was the only crop he knew how to grow, and every year he could count on a profitable harvest. Then again, he realized how things would go if he did nothing.

“It was either going to be a shopping center or a trailer park. I didn’t want either of those things to happen to my family’s land,” he said.

He set aside 10 acres and planted Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay grapes. Then he waited three years for the vines to bear fruit. Meanwhile, huge fermentation tanks needed to be bought and a pleasing tasting room constructed. The climate proved not to be exactly similar to the best European wine regions he had been told it was. Grape vines didn’t always thrive in the clay-loam soil, temperate climate, southern humidity, and heavy seasonal rainfalls.

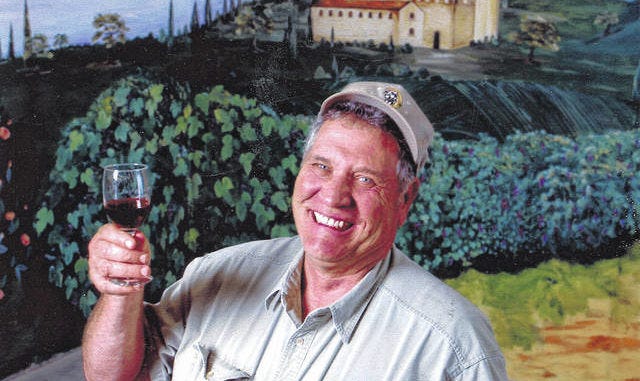

He was lucky, though. He steered his first grapes through the additional four years it took before his wine approached drinkability. He named his vineyard RagApple Lassie after a prized cow he raised as a boy in the local 4-H club, and, by 2008, his wine began to make a name for itself. Hobson now also grows Shiraz, Sangiovese, Pinot Grigio, and Pinot Noir grapes. You can meet him and his wife on most days hosting visitors in his homey tasting room or leading tours through the fermentation facilities. A new patio overlooks the kind of idyllic landscape that encourages a languorous hour or three sipping through a bottle or three.

There are now 48 well-regarded vineyards in the area, stretched out along what has become known as the Yadkin County Wine Trail. Spring to fall, and, if the weather holds, into winter, bus tours wobble along, dispensing increasingly inebriated passengers from one winery’s tasting room to the next. A popular time to begin the road trip is around the vineyards’ Sunday morning brunch hour, now that a 2017 local ordinance allowed wineries to serve liquor before noon.

Many of the vineyards are still owned and operated by the original farmers, but outside investors have established a presence and sharpened competition. There’s no question that the buyouts helped to preserve family farms. But it is increasingly transforming the area’s uniqueness.

A similar tale can be told about Napa Valley. Vineyards have a long history in the valley, but it remained localized, woven into the culture of the surrounding rural, tightly knit communities. The fields sustained the owners and those who worked the fields. Towns supported an economy that took care of most everyone’s needs. It wasn’t perfect or equal, but life in the valley held fast to a viable social compact.

Rapid changes began a little more than 70 years ago. Today, and especially on weekends, Route 29, the two-lane main road that runs through Napa, resembles any urban traffic clog. In 1950 there were about 20 wineries. Now there are at least 375, most of them huge, with an international owner base, their tasting rooms hard to distinguish from one another without prominent signs along the way. Without a doubt, a tour is a very lovely way to spend an afternoon, but a price has been paid, especially for the field workers who can no longer afford local housing and the intensifying impact on the region of the fire season and climate change.

It will be a long time before Yadkin Valley approaches Napa or obtains its cache in the wine world. But it took only 20 years for it to evolve from its tobacco roots. Many family farms were saved. New economic opportunities revitalized an area hard hit by falling market prices and closed factories. But what’s happening has already slashed through a unique culture, and that’s something to take a moment to contemplate.