(That photo on the homepage? Not us. We dream about being this young and beautiful! It’s the work of terrific photographer Jose- Maria Moreno Garcia who took it at the fiesta in 2014.)

Hey all, sorry this is so late. Excuses include the editor taking a huge amount of time (he’s very thorough) and various computer problems which required toggling between three different systems. I’m finalizing this from my phone. In any case, hope you like the following travelogue.

The saffron celebration, Fiesta de la Rosa del Azafran, is happening this weekend in the small town of Consuegra, Spain. My sister and I attended it 20 years ago when I was writing a book about saffron. At the time I thought the fiesta would be a fitting way to bring in Spain’s history and identity with the spice. It would also be an excuse for us to travel together, and what’s better than to go to Spain in autumn?

But since then, especially in the last couple of years, the fiesta has become more internationally known and written about, including in the Substack newsletter, Food and Fiesta. The event writes itself and all the accounts I’ve come across will give you a good overview of the weekend. All I can add is the distinct experience of two middle-aged American women wandering around a very small Spanish town in the middle of nowhere. A condense narrative follows:

I asked my sister Sue to come along because she’s more comfortable out in the world than I am, a savvy traveler, and knows enough Spanish to get by. Most importantly, she’s great fun. (If you don’t have a Sue in your life, she will gladly join your trip.)

We really didn’t have the money to suddenly fly off to Spain for three days and the air flight tickets wipes out a considerable amount of our travel funds. We will take two buses to get to Consuegra. By the time we’re deposited in Toledo, we are snapping at each other from hunger. Sadly, it’s siesta time. The bus terminal’s cafe is closed and the streets outside are vacant, not a sound around, or an open door in sight. Except there, in a little alley by a church, we find a narrow grocery store, late in closing up, with loaves of freshly baked bread, cheese, and wine. Salvation!

Eating said purchases on the steps of a church is frowned upon by the one person who is not napping—a policeman. Rather than plead our case, we return to the terminal and spread our meal across a couple of plastic seats.

The second bus leaves us on the side of the road. The inn we are staying at should be right across the street. Instead, there’s a gas station blaring out the Rolling Stones’ Sympathy for the Devil. The single person in sight is a woman in a black dress, accented by a gaily patterned apron tied tight around her waist. She is headed for the cemetery down the road, arms full of flowers.

A police van pulls up (you may wonder what's up with all the policemen following us about? We did, too). The two officers inside immediately understand our situation and are amused because the inn is right around the tall hedges across the street. They wave goodbye as we pull our suitcases toward the hedge.

The one person at the inn who speaks English is the chef, an impatient translator, especially during his dinner preparations.

The inn is the only place that was not completely booked for the saffron festival. It’s a mile outside town which may explain why it is cheap and has rooms. But its rural setting is charming and the staff attentive. Despite the mattresses that wrap around us like burritos, we conk out as soon as we drop our exhausted body into them.

Right at dusk, we pull ourselves together and walk the mile to the festival.

The road which runs between harvested fields, is not lit and does not have anything resembling a shoulder. This means we have to dodge out of the way of two cars and a tractor. It makes for a bit of a tricky two-step dance.

Once in town, past the toy store whose windows are crowded with a menagerie of gleeful mechanical toys and a rather desolate park filled with old men crowded together on wooden benches, we come upon a narrow stone bridge. It once spanned a river that was drained after 1891 when it flooded the town and killed 400 people.

Finally, we are in Consuegra! The town is situated on a plain, overlooked by its famous windmills and a Medieval castle on a ridge of small mountains in the distance. The claim is that Don Quixote battled one of the 11 windmills. None of them are turning now. The castle offered a sweeping view of the invaders who charged toward the town. It wasn’t around when the first attacks came. The Romans were first, then the Celtics and Visigoths. All the conquerors left archeological and cultural traces behind. The Moors built the castle when they arrived in the 700s. They were the ones that planted the first saffron fields. The castle didn’t help them, though, when battalions of Spanish knights, fresh from a crusade, stormed it in 1182.

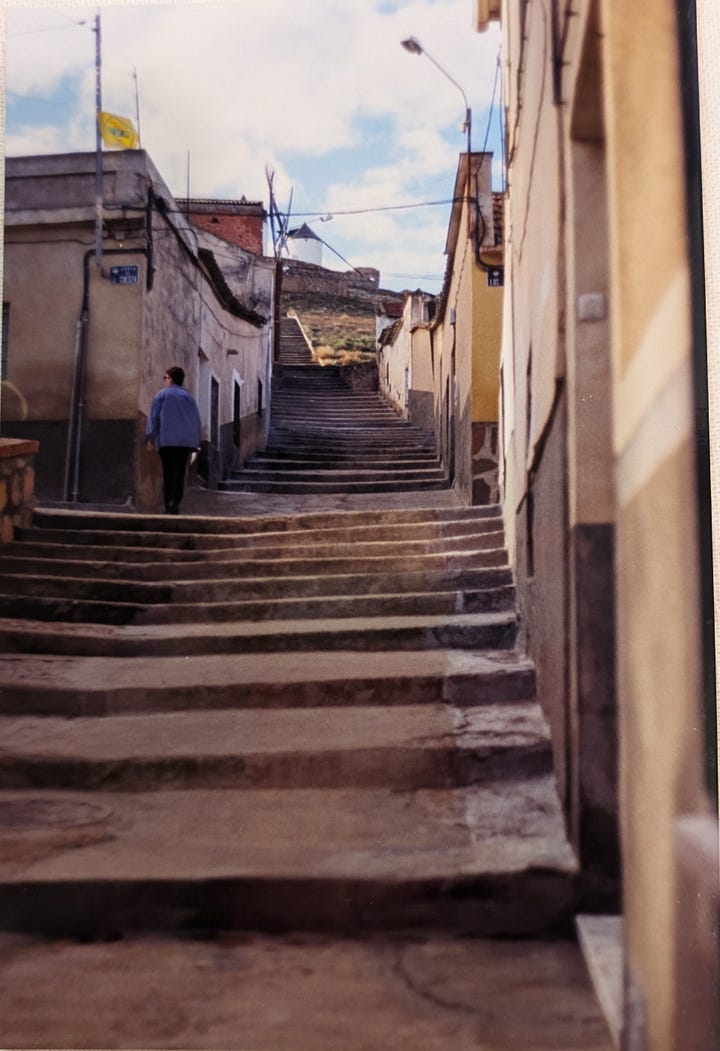

The tourist office is in one of the windmills. The path incorporates at least a thousand well worn stone steps, then a steep road you can drive up. Otherwise, leave your fashionable heels behind.

Damn steps up to the windmills then down to the town. The windmills are truly amazing, especially at dusk when their white plaster walls capture the dusk’s purple light. We find the tourist office (and gift shop) manned by a bunch of local university students. They appreciate Sue’s mangled Spanish and load us up with brochures, maps, the events schedule, and a fiesta poster.

Sue understands that we need to run back down the steep steps to catch the crowning of this year’s Dulcinea. She is a charming, slightly embarrassed 15 year old, dressed in a splendid brocade Medieval gown, her thick brown hair caught up in strings of pearls. She’s surrounded by seven ladies-in-waiting, equally young, equally embarrassed and just as excited.

After the fiesta’s Dulcinea is crowned, my sister demonstrates one of her best talents by finding the most lively bar. She’s equally skilled at ordering us an array of tapas and glasses of wine. We don’t know what most of the dishes are but everything is fabulous.

About half way through cleaning our plates, five American youths on their year abroad sidles up to us. Since Sue and I have children their age we feed them. At some point, the most roguish among them reveals they have been sleeping on the ground beside a windmill. Couldn’t they sleep on our room’s floor, instead?

Well versed in teenage wiles we say, sorry, nope. Besides, sleeping on the ground is mandatory for anyone’s year abroad. To make it up to them, we order more tapas and a last round of wine.

No moon nor stars light the road back to the inn. Instead, the sound of Iron Butterfly’s In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida blasting from the gas station guides us. Thank God our room is at the back of the inn.

Next day, while hanging out at the Plaza de España we meet Paco, the mayor, a tiny, energetic old man who founded the fiesta in 1969; three ancient stout women clad in black, one of whom pins two small saffron crocus on our shirts and demands a handful of change; and an industrious Japanese TV crew that’s pushing everyone out of its way. Sue disappears into the crowd and returns with Ellen Szita, a world renowned saffron expert. Ellen, possessive of all things saffron, doesn’t much like hearing about what I’m up to, but she’s kind enough to impart a long lecture on all kinds of saffron/Consuegra information.

What a hoot, Sue says after Ellen scampers off to tag along with the Japanese TV crew.

The best part of the day: the cook-off in the park. A ring of contestants (that year numbering 10) cooking something in cast iron pots nestled in or strung above small camp fires. Saffron, of course, is a required ingredient. Not everyone is making paella. There’s gallina pepitoria, a traditional regional dish influenced by the Moors that requires a chicken somewhat past her fertile years. Rice dishes and bean stews simmer in clay pots buried in the embers. Plus, a whole lot of wine. The judges are a celebrated TV personality, a cooking teacher, and Mayor Paco. Five very inebriated young brothers are pronounced the winners with their sausage paella. They kiss all the judges and one swoops up the cooking teacher into his arms and whirls her around a couple of dizzying times. Then forks are handed out and the crowd rushes forward, diving into every contestants’ pots.

The famed saffron-picking contest happens after everyone’s siesta in the courtyard behind the Plaza de España. Nine women and one man sit behind a long table, each with a pile of blooms for them to harvest the flower’s three saffron stymies. Most of the older women are dressed in bulky black sweaters and wear their hair short perhaps to show off their beautiful, heavy looking gold dangling earrings. Most of the younger women are colorfully dressed and have dyed their hair in one or three of the rainbow’s colors. The man, who looks to be in his late twenties, is quite corporate in a blue button-down oxford shirt. Mayor Paco is the grand master. He gives a signal and the women commence the careful operation of picking the saffron stymie from the center of the delicate petals. In contrast, the man rips into his pile strewing the blossoms every which across the table.The contestants fingertips quickly stain yellow. In the end, the women look perturbed that the man finishes before them.

Because my sister and I did not trudge back to the inn for a siesta, we’re now exhausted. The best way to revive, of course, is to discover a small restaurant whose leather banquettes look very alluring. We are warmly greeted, escorted to a table beside a window glazed by a bit of sun, and slip our shoes off under the table. Late lunch consists of two different bocadillos and, of course, a carafe of red wine, finished by very strong coffee.

Not quite revived, not quite dead, Sue and I gamely trek once more up to the windmills for the fiesta’s final event: the ceremonial starting up of one of the windmills. After three attempts to rev up the wooden gear, everyone hoots and hollers when the blades finally start slowly turning.

That night, the chef at one of the fancier hotels offers a saffron-inspired menu. We figure the meal is a necessary expense for our research trip. Sue orders a very traditional, Moor influenced, dish (chicken al Andelua). I’m not saying I’m played out, but I decide on the only item without saffron—conejo en escabeche. And a bottle of wine.

My sister chats up the couple at the next table. The wife’s family used to grow saffron in the valley but eventually plowed it over to plant olive trees. The husband grew up in Granada (“the most beautiful city,” he boasts to which his wife rolls her eyes). He’s happy to accompany her each year to the fiesta and listen to her family reminisce about old times.

It’s very, very late by the time we pay the bill and start the return to the hotel; in about five minutes we lose our way. Sue thinks we’ll be able to ask for directions in a bar that happens to be filled with only men and they are not pleased at the sight of us in the doorway We take the hint and resume wandering the street when our path is eventually crossed by a pre-teen coming out of a late-night shop with a container of milk. He judges that two slightly tipsy middle-aged women is not a good thing so he leads us to his house where he explains the situation to his father. We can only smile our contrition. He exchanges slippers for shoes and we follow him outside where we squeeze into the back of a small car; his son in the front seat. The father deposits us at our inn’s door where all its tenants have gone to sleep a long time ago.

We awake 10 minutes before the bus to Madrid pulls up to the hedge hiding the inn.

The Sunday 9 a.m. non-stop bus from Consuegra to Madrid will not wait for you if you are a second late. It will, though, if you throw yourself against the door. Then the driver will open it and, with an irritated tone, yell, “darse prisa!” If you’re with Sue, she’ll say to the driver, “lo apreciamos mucho.” He’ll then smile and close the door and off you go to the Madrid airport.

Afterword

Neither my sister nor I have been back to Consuegra’s saffron fiesta since then. From what I see online, the town has prospered, its windmills and the fiesta bringing in many tourists. I couldn’t find any mention or images of our little inn nor the gas station across the street. In fact, it seems the area is no longer rural. I hope the fiesta’s Dulcinea is still an embarrassed teenager. I wish I could see again the windmill turn and rest my feet under a comfortable restaurant’s table while lunching on a good thick sandwich washed down by a rich red wine. I hope there are college students still camping out on the ground beside a windmill. But you know what I would love most, beside traveling with my sister again? I would give a great deal to be whirled around a cooking fire by a young man who’s dish just won the prize.

Already a subscriber? Upgrade and receive a special gift!

What a grand and fun adventure!

Love it! 😂